Indian Council of World Affairs

Sapru House, New Delhi‘Inequalities, Remittance Cost, and Indicators of Progress in the Global Compact for Migration (GCM): Decentering the Global Migration Governance for Academia, Private Sector and Government’

In the recent months of June and July 2023, I had the privilege of engaging with three global events on international migration:

- Delivering the inaugural keynote address at the opening plenary of 20thAnnual Conference of International Migration, Integration and Social Cohesion in Europe (IMISCOE) at Warsaw, Poland, 3 - 6 July;

- Sending a video message to the UN’s International Day of Family Remittances commemorated on the 16thJune followed by an interview in the GRFDT online expert dialogue series, and

- Participating in the five regional online consultations with Member States and Civil Society Organisations, on choosing the indicators for measuring the countries’ progress on the Global Compact for Migration (GCM) Objectives, convened by the UN Network on Migration, 24 – 28 July in preparation of the forthcoming SDG summit in September, 2023.

What is common in all three events is that they all pertain to the fulfilment of the GCM objectives by the time SDGs period gets over in 2030. The purpose of this guest column is to share my reflections on them from the perspective of decentering global governance of international migration for its three major stakeholders, viz., the academia, the private sector and the government.

1. Decentering Migration Studies from Development to Distribution:

The 20th Annual Conference of International Migration, Integration and Social Cohesion in Europe (IMISCOE), the world’s largest network association of migration scholars, hosted by the University of Warsaw, Poland from 3rd to 6th July, 2023 was organized on a challenging topic of “Migration and Inequalities: In Search of Answers and Solutions”. A remarkably large audience of 950 in-person and 400 online participants from across the world attended the conference. I began my keynote address by saying that while inequalities have been a gift of nature and migration the leveler, the barriers to migration have been mostly man-made! Had there been no inequalities, perhaps most of the migration would not have existed. I added to say that to me the conference marked the beginning of a remarkable paradigm shift from the two-decade old multilateral focus upon the catchphrase “Migration and Development” to that on “Migration and Equality”. I also said that it should now be ushering in a turning point in the migration discourses in multidisciplinary research and hopefully eventually in interdisciplinary and transdisciplinary research, the three being different from each other despite being understood in an overlapping way if not interchangeably. In this context, I further added that in my own social science discipline of economics particularly, this would mark a remarkable change of gear from the talk of maximizing Growth and Development a la Development Economics to that on optimizing Distribution and Welfare a la Welfare Economics towards uplifting the standards of living and quality of life, the two universal agendas across the north and south divide.

I refreshed the collective memory of the migration scholars that the challenges of the 20th century underdevelopment had given us the MDG, the 8 Millennium Development Goals (2000 -2015), confined to the betterment of the global south in autarchy, i.e., exclusively of any intervention or support from the global north. However, whether we noted or not, it assigned no leveler role to migration in uplifting the global south closer to the global north! Rather, it was the notion of mutually exclusive sovereignty of national borders that prevailed to keep human mobility at bay from global multilateral negotiations. It was the then UN Secretary General Kofi Annan’s ingenuity to constitute a Global Commission on International Migration (GCIM) that initiated the piggy-backing of global human migration on the Global Development Agenda, the blue-eyed baby of multilateral diplomacy that no one would have raised any objections to! Subsequently, the MDGs gave way to the sustainable development goals, the SDGs (2015 - 2030) with equal partnership of the global north, but ironically, “migration” per se again missed the bus in being excluded from among the latter’s 17 stated goals. The grapevine consoled us into looking, frantically, through a microscopic combing of the 169 Targets to find out if there was a word related to the term “migration”. Happily for the multilateral diplomacy of course, we were made to discover Target 10.c which was aimed at “reducing transaction costs of remittances for the migrants” from above 5% of the value of transaction to under 3% listed for SDG no.10 as follows: “To reduce Inequalities within and between countries.” (emphasis added) This subsequently lay embedded at the core of the GCM 2018 objectives, and it is the Warsaw Conference that has jacked it up multifold in significance for the academia’s newfound decentered agenda with the new catchphrase: “Migration & Inequalities”.

To pursue the subtitle of the conference, viz., “In Search of Answers and Solutions”, the first and foremost challenge for us social scientists then would be: What New Theoretical Questions to ask about the changing relationship between Migration and Inequalities? It is not easy and simple to devise newer theoretical questions every time a migration-impacting crisis challenges us, e.g., the Economic Crisis of 2007-8; or the COVID-19 Pandemic. Our second challenge would be: How to pursue overlapping theoretical frameworks of various social science disciplines, viz.,

- History (Times),

- Geography (Regions),

- Anthropology (Cultures),

- Sociology (Identities),

- Political Science (Belongings),

- Law (Justice),

- Philosophy (Ethics),

- Economics (Resources) and

- Psychology (Emotions), and others…

I observed that it would be interesting to examine two things:

- How many and what proportions of researchers from each of these disciplines are pursuing a career in the field of migration and how those have changed over time in the Global North and the Global South.

- It would be more interesting and more challenging to identify and count those who are working at the boundaries of more than one discipline by bringing down the walls between them like, for example, the Non-economist awardees of the Nobel Prize in Economics, Daniel Kahneman a psychologist (2002) and the first woman awardee Elinor Ostrom, a political Scientist (2009).

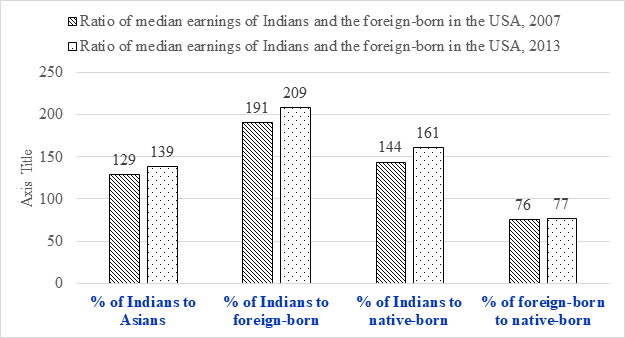

I have seen some progress in multidisciplinary efforts, of bringing together complementary or substitute perspectives on the same platform of a workshop or a conference. For example, the recent CERC in Migration and Integration Annual Conference on Narratives, and a workshop on Datafication of Borders that took place at the Toronto Metropolitan University, Canada where I was a Scholar of Excellence visiting professor. However, what continues to be a lingering challenge of the 21st Century is the task of integrating into an intellectually cohesive (or holistic) methodology of truly interdisciplinary framework. I said that the disciplinary boundaries have rather become more divisive with growing tensions of what I would call the Interdisciplinary Envy, Fear and sometimes Contempt for each other’s methods, and it would be a challenge for our future generations of scholars to reverse that trend. Looking at the topics of the sessions and profiles of speakers and presenters in terms of their cross-cutting interests and specialisations, we could draw upon them to build a rich repository of truly transdisciplinary questions to ask about the 21st century challenges of migration and inequalities. How shall we identify and how shall we measure our dependent and independent variables would be the basic steps to answering those questions. This is because many a time our cause-effect relationships are reversible, as for example, the following two sets of data would show:

Figure 1: Inequalities Within A Country (USA)

- Ratios of annual median earnings (USD 000) of the India-born, the Asia-born, the Foreign-born and the Native-born in USA: 2007 and 2013

- Sources: US Bureau of Census, ACS (2015)

Source: Author, using 2007 and 2013 data from the United States Census Bureau (2015), American Community Survey (ACS).

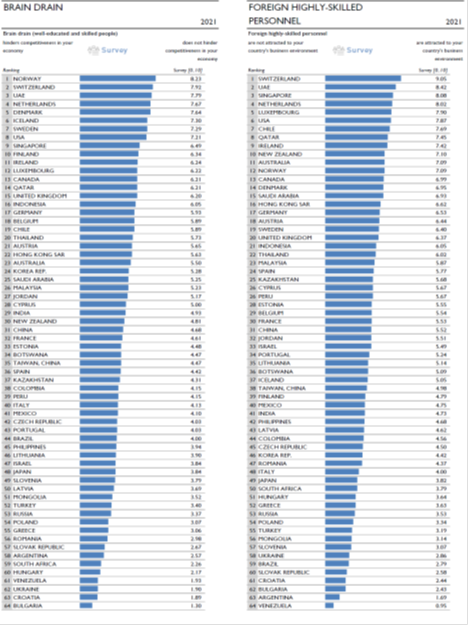

Figure 2: Inequalities Between Countries

BRAIN DRAIN BRAIN GAIN

Source: Khadria, B. (2022), “Did catchy slogans and future commitments in the IMRF reflect poor implementation of the GCM?”, paper presented in the panel "Taking Stock of the Global Compacts" at the International Workshop on “The Present and Future of the Global Compacts”, organised by Canada Excellence Research Chair (CERC), Toronto Metropolitan University, 7th June.

Such data may be subjected to interdisciplinary inquiries into new inequalities arising from a number of emerging challenges, for example,

- Demographic changes in AST;

- Climate Change and displacement;

- Technological Change including skill-biased technological change (SBTC) and artificial intelligence (AI), educational redundancy and unemployment;

- Post-COVID-19 change in mortality and morbidity; and

- War-led Mass Forced Migration of Refugees and galloping inflation.

I emphasized that effective answers and solutions to these challenges would require two conditions to be met. To use the language of economics, these are:

- A necessary conditionof building upon existing knowledge (such as “Pareto Optimality”) to come up with Innovative Ideas, and

- A sufficient conditionof Introspection to keep those innovative ideas free from the temptation of what I may term as Interdisciplinary Plagiarism, by which I meant sourcing terminology and literature from another discipline without proper and complete acknowledgment!

Otherwise, I concluded, it would be like the well-known simile of six blind men trying to describe an elephant but each one mistaking a part of the animal as some other known item! In other words, we the academia shall otherwise have to remain content with a Partial Innovation of the 21st Century Challenge of Inequalities, but not the whole picture!

2. Decentering Remittances from Migrants to Markets:

My video message on remittances to the UN’s International Day of Family Remittances commemorated on 16 June and my video interview to Development Economist and Vice President of GRFDT Ms. Paddy Siyanga Knudsen of Zambia that followed were to highlight the known positives and the lesser-known negatives about the transfer of money home by the migrant workers to their families. The three issues that I said needed attention were Multiplier effects of transaction cost reduction in remittances, Dark side of remittances, and Silent backwash of remittances.

The video message that I sent to the UN event held at Nairobi was the following: “This is a good time to talk about remittances particularly in the context of the forthcoming events, viz., the SDG Summit, the Global Compact for Migration and the Global Forum on Remittance Investment Development Summit 2023 as well as International Day of Family Remittances. What I think particularly important is that the discourse on remittances has been given enough time and scope for discussion on the levels of remittances received by different origin countries of migrants and how the monetary resource should be utilized in the countries of origin of migrants. What we have not discussed so far is why should remittances be subjected to financial inclusion and why the cost of remittances be brought down below three percent. I think it is important to understand this particularly when there is a perceived conflict of interest between the parameters of the receiving families and the companies operating in the business of money transfer. One benefit of bringing the cost down is that it will increase the disposable income in the hands of the families. This I think is a very important point to keep in mind because it is going to compensate the firms for reduced profit when they bring down the cost because they will then have a larger market with higher purchasing power in the pockets of the families, raising their ‘effective demand’ and thereby actual consumption.

On the other side, alongside celebration of the remittances, we also need to talk about the negative side or the darker side of remittances. The latter because the construction of remittance takes place through reduction in actual consumption by the migrant workers and thereby reducing their nutrition, having adverse effects on their health conditions, and on their living and working conditions – all leading to reduction in the labour productivity which actually leads to a reduction in the overall national income of the country concerned.”

Now, to draw upon my subsequent conversation with Paddy Siyanga Knudsen, I would like to provide a bit of background as to where we stand today on the International Day of Family Remittances. The campaign slogan for this year's commemoration around digital remittances is aimed at (a) financial inclusion and (b) cost reduction. A huge amount of US$ 647 billion is reported to be passing through the financial transactions, which is expected to increase to 5 trillion US dollars in about seven years when the SDGs would come to a close, in 2030. Indeed, there is a link between the commemoration of International Day of Family Remittances and the GCM objective 20, which is about reduction of remittance costs in the Foreign Exchange and Money Transfer Markets of the remittances industry. From among the concerned stakeholders in the communities that is now termed as the “whole of society”, there were many private sector players at the UN’s Global Forum on Remittances Investment and Development that took place in Nairobi with over 600 delegates from around the world.

What is required is to unpack an optimally balanced perspective on remittances with the objective of improving the conditions of millions of migrants and their families, at the same time keeping in mind the business interests of the private sector. In other words, we need a better understanding, from a migrant's point of view, about the financial inclusion and remittance cost reduction by asking where is the GCM objective 20 critical for remittances to facilitate better livelihoods for the migrants’ families? The stated objective of reduction in remittance cost is from the present 6% and higher up to the UN’s target below 3%. How this cost reduction matters to the migrants is a very important question that we usually do not put our minds to. Instead, we have so far concentrated on the macro data in terms of the volume of the remittances that are coming to the origin countries of migrants. We satisfy ourselves simply by looking at the World Bank and IMF league tables of the rankings of countries and how they are changing year after year in the first, second, third, fourth and fifth positions. In terms of the migrants’ point of view, if the transaction cost in the formal transfer channels were brought down, then it would help the migrants shun the informal channels of the hawala market, which may be offering service at lower transaction cost, and even unstated guarantee of safe practice. A reduction in transaction cost would leave more purchasing power in the pockets of the families using the formal channels, which would have a multiplier effect on the market. The revenue lost by the private sector agencies in reducing the transaction cost in the formal money transfer market will thereby ultimately come back to expand the overall market size and would not end up becoming charity but an act of self-interest leading to a win-win situation. It would also become a matter of concern to the migrants as responsible citizens when the shift to the formal channels would definitely help in nation building through reduction of black money in the informal market, with ramifications on the welfare budget of the state for providing public utilities like water, sanitation, roads as well as social services like education, health and housing to the left-behind kith and kin of the migrants as well as to the returnee migrants themselves. This will not only lend greater legitimacy to the voice of the migrants in civil society, but also boost their feel-good-factor and thereby average state of mental health as active participants in nation building. Think tanks like the GRFDT and, of course, the young scholars who can influence the policy makers through their writings, debates and campaigns along this line of argument and persuasion can thus supplement the purpose of the International Day of Family Remittances.

We also need to keep in mind that the cost of remittance is a per-unit rate on the amount transacted, which may be inversely related to the volume of remittance transacted. There is no contradiction because if the volume is large then the rate can go down without adversely affecting the total profit the market generates for the dealers. When the global volume of remittances is rising year after year then the total profit would also rise even if the rate of cost is lowered, thus leaving more disposable money in the pockets of the families receiving those remittances thereby leading to expansion of the overall market of goods and services consumed by them. This should ameliorate the fear and suspicion that cost reduction for remittances would lead to lowering of the take-home profit as the disposable income of the managers and owners of the money transfer business enterprises, be it in the private sector or the public sectors. In short, the rationale behind the argument for cost reduction is the win-win outcome on both the demand and supply sides of the money market, thereby leading to enhancement of overall welfare for the “whole of society”.

For example, at the Nairobi Forum, there were important experts and practitioners starting from Central Bankers all the way to people who work with the payment systems and facilitate remittances to move from one space to another. There were also awards for instance that were given to the digital finance industry dealing with the remittance market in the international space, particularly the Central Bank of Gambia and Central Bank of Kenya for their exemplary work. The Central Bank of Gambia was very prompt to dedicate its award to migrants and to the diaspora in recognition of their contributions. Often, we forget that this is a billion dollar industry of money transfer with dominant private sector players, which is out there, interacting either positively or negatively with large parts of people’s disposable incomes.

As mentioned earlier, it is also extremely important to demystify talking about what I call the “dark side” or the negative side - the lesser-known facts about the dynamics of remittances. For this, one has to go into the process of construction of remittances as to where do they come from. They come from the income and wages that migrants earn and save in the country of destination. To maximize those savings, the migrant workers cut into their basic minimum needs of consumption, medication, nutrition, housing and so on by making big compromises. To my mind, I think the private sector, as part of “the whole of society” needs to try to put these mechanisms together about how the dark side can be turned into a bright side by bringing the cost of transaction down to the optimum level. At the same time, there has to be mechanisms for providing guarantees, securities and insurance to the migrants’ remittances that if something went wrong then there would be some other agency, maybe the government itself or other private sector insurance agencies to take care and provide security. This, I think, will create the trust that is an essential ingredient – trust in the diaspora, in the banking system, in the government, in the bureaucracy, in fact in “the whole of government”.

When it comes to the “whole of government”, I think it needs to be disaggregated into its three major components, viz., the legislature where the politicians as policy makers come up with the policies, the bureaucracy that executes the policies in the field, and finally what we have not brought in substantially so far, the judiciary. The judiciary is our moral guard that I think we need to activate much more and get involved into telling the private sector what is natural justice and what is not ethical. This I think is extremely important so that when we talk about the whole of society or the whole of government, then it should not just start with the catchphrase and end with the catchphrase. Both need to be deciphered to understand properly as to what their different components are and where the conflicts of interest are. None of the three agencies in the “whole of government” need to lose patience for the results and rush if one had to wait a longer time. What is extremely important, I would say, is to extend trust, time and loyalty to each other to actually leverage the benefits of bringing down the transaction costs, with multiple ramifications and the multiplier effect that can influence the “whole of society”.

I would also like to draw attention to the fact that while we have been asked to talk about the “whole of society” and the “whole of government”, we have not been asked to talk about the “whole of migrant”, and this shortchanging has been allowed despite my pointing out verbally as well as in writing at the IMRF in May 2022. I am glad that the word “family” is included in the International Day of Family Remittances so that it is not only the migrant worker but also the migrants’ spouses and their children who are included. I would rather go one step further to include the grandchildren of the migrant in the next generations on the one hand, and parents and grandparents in the preceding generations. What is important to note is that they comprise the entire extended family of the migrant, particularly in the close-knit societies and communities of the global south, who all can turn out to be the beneficiary or non-beneficiary of the remittances. I would say that if any of them is deprived of these rights and privileges then we are not talking about the “whole of migration” but only a part of it.

I have three more points to draw attention to. First, the democratic culture in the receiving countries is important in the sense that a democratic institution has a link with the transfer of remittances that takes place through formal channels. Even if remittances are not to be taxed, there has been some demand at some point in time that the destination countries are being deprived of these resources when money is transferred to the origin countries. This is ironic because it is tax-paid post-tax savings that the migrants are sending home. When they go through the informal channels of the hawala market, it is the business or corporate tax due to the origin country government from the operators that gets lost through evasion. The transferred money turns into black money and it is then that the principle of democratic functioning of society or state in terms of its revenue and its expenditure on welfare activities get distorted. Therefore, I think it is important that formal channels are made affordable because if they were more expensive than the hawala market then people would naturally resort to the parallel market, leading to weakening of the democratic institution of the welfare state.

Secondly, there is the question related to the undocumented migrants. It is unfortunate that some surveillance on migrants has been linked to such point of contact with the system that includes money transfer. Therefore, undocumented migrants have developed their own sensors in order to avoid being detected by the authorities and then rounded up and subjected to hardships of return to foster homes for reform or deportation. It is amazing how efficiently the hawala system capitalizes on trust, for example in somebody using the hand-to-hand informal transfers without fear of being reported. Otherwise, without the element of trust they will remain as a black hole that migrants will tend to avoid. Therefore, I think, the issue needs to be approached from the point of building trust. I think access to formal channels of remittances should not be based on the legal status of the migrants, nor should access be considered an act of charity to the migrants. Rather, it is important to first estimate what proportions of people or migrant workers or families are undocumented and how much they earn and save and what proportion of savings they can remit home.

My third point is whether we should incorporate the issue of remittances from the global south to the global north. For example, there are many parents in the global south who finance the studies of their children in countries of the global north. Similarly, huge amounts of money are transferred to many immigrant entrepreneurs in the north who rely on the resources of their families back home in the global south when they invest in the startups in their destination countries. Hence, the reverse remittances from the global south to the global north or from the origin countries to sending countries must also be put on the multilateral agenda of migration governance. A few years ago, around 15 percent of the remittances coming from the north to the south used to go back to the north countries for financing education of international students only. Foreign students comprise large section of the international migrants and 65 percent of their cost of education comes from the pockets of their parents whether from their own savings or from loans taken on interest. Only 10 percent of the funds come from the destination country sources and the remaining 25 percent from the third-country sources, which are mainly the charity organisations. In addition, there are reverse remittances which support the startups and other enterprises set up by migrant professionals in the global north destination countries. The latest surge in reverse remittances are due to introduction of investment visa and offers of permanent residency and citizenship to those immigrants investing large funds and creating employment in the destination countries of the global north. All these flows of reverse remittances need to estimated and projected. I had called them the “silent backwash of remittances” because no one talked about them and they were not the issues to be discussed under the global agenda of migration and development. Therefore, it is now important that we connect these links and look into the construction of the remittances with different probabilities and proportions flowing back to the countries of destination.

3. Decentering Governance of Implementation from Objectives to Indicators

The five regional consultation sessions on indicators of measurement of progress in achieving success with the 23 GCM objectives took place between 24 – 28 July, in coordination with preparations for the forthcoming SDG summit in September, 2023.[i]

In paragraph 70 of the Progress Declaration of the International Migration Review Forum (IMRF) that took place in May 2022, Member States requested the UN Secretary-General to propose two things: (i) a limited set of indicators to review progress related to the implementation of the Global Compact for Safe, Orderly and Regular Migration (GCM), by drawing upon the global indicator framework for the Sustainable Development Goals and targets of the 2030 Agenda, and (ii) to include a comprehensive strategy for improving disaggregated migration data at the local, national, regional and global levels. The United Nations Network on Migration workstream on "Development of a proposed limited set of indicators to review progress related to GCM implementation” was established to address this request. Throughout 2023, the workstream will be focusing on the development of a proposed limited set of indicators, whereas in 2024 it will prioritize activities related to the comprehensive strategy for improving disaggregated migration data. The resulting proposal will inform the biennial report of the Secretary-General that would follow in 2024.

The workstream is led by the United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs (UN DESA) and the International Organisation for Migration (IOM), and it comprises, as of June 2023, in addition to these two co-leads, thirteen other members, notably including my own organization the Global Research Forum on Diaspora and Transnationalism (GRFDT). The remaining twelve members are: Gender Hub+, International Fund for Agricultural Development (IFAD), International Labour Organization (ILO), International Trade Union Confederation (ITUC), Mayors Migration Council, Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights (OHCHR), United Nations Development Programme (UNDP), United Nations Population Fund (UNFPA), United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR), United Nations International Children's Fund (UNICEF), World Bank, and World Health Organization (WHO).

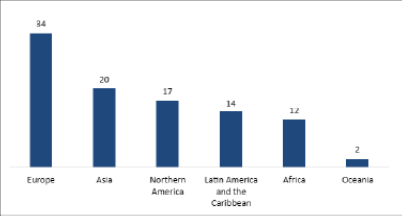

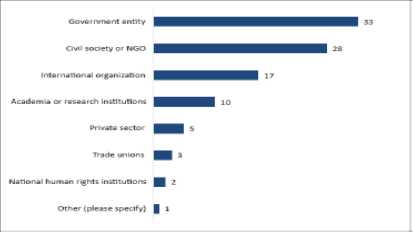

To gain insight into the critical elements to be reflected in the proposal for a limited set of indicators, the workstream conducted a canvassing questionnaire in February 2023. Member States, international organizations, and stakeholders, altogether numbering ninety-nine responded, sharing their views on the scope and criteria. Important among the endorsed criteria to develop the proposal for a limited set of indicators are: complying with existing international standards and recommendations; providing a basis for international comparison among countries and regions; and getting used to monitoring the progress over time. Figures 3 and 4 show the region wise and type wise distribution of the entities responding to the canvassing questionnaire.

Figure 3: Number of responses by region

Figure 4: Number of responses by type of entity

Although the summary of the responses to the questionnaire is yet to be compiled and made available for comments, I have two key observations to make:

- While the entities agreed on other points, there was a difference of opinion about additional budgetary implications of the indicators exercise. Whereas most government entities (i.e., whole of governments) called for no additional budgetary implications, most international organizations and stakeholders (i.e., whole of society) respondents have considered additional budgetary implications to be a critical element.

- The eight South Asian governments - Afghanistan, Bangladesh, Bhutan, India, Maldives, Nepal, Pakistan, or Sri Lanka – representing the most important origin countries of the largest number of migrants in the world are yet to respond to the questionnaire. Among the academia or research organisations, there is only one, that from Nepal, viz. Nepal Institute of Development Studies (NIDS) who has responded so far. The other one, my own organization from India, the Global Research Forum on Diaspora and Transnationalism (GRFDT), is anyway a member of the workstream and hence not to be counted.

Concluding Remarks

Decentering the global governance of international migration on the three platforms of the academia, the private sector and the government has seemingly become the imminent tool for optimal implementation of the 23 GCM objectives within the broader goals of SDGs by 2030. It is here that I find the world of migrants being poised at turning points for both the destination and the origin countries as the “hubs”and “hinterlands” of human mobility in general and for India as the world’s largest hinterland specifically. India, with a large size of the higher education academia, large size of the public and private market, and federal democratic structure of government, has the potential to be the world leader in decentering the implementation of GCM agenda of good governance from where it is presently focused to where it should be in the future. All the three agencies of its academia, the private sector and the government must look outside the stereotypes in global migration and step into the realm of innovations. The potential of paradigm shift also calls for India to become a hub rather than remain a hinterland of migration, both for the knowledge workers and the service workers. This would require persistent trust, time and loyalty to the challenges that lie in the path to the target. Before changing the global agenda of international migration governance, can India devise a holistic migration policy that it can showcase to the world in the multilateral fora? Finding an appropriate answer to this question would open up multiple paths of probabilities for India to tread.

*****

The Author is former Professor of Economics, Education & International Migration, Jawaharlal Nehru University; presently he is President of the Global Research Forum on Diaspora and Transnationalism (GRFDT). The author acknowledges the gracious invitation extended by the IMISCOE Conference Convener Pawel Kaczmarczyk to deliver the keynote address. He is also indebted to Paddy Siyanga Knudsen, development economist from Zambia; Rachid L’Aoufir of Transnational Corridors e.V. from Berlin; Iman Ahmad, public health expert from Toronto and Manjima Anjana from the University of Hyderabad for raising important points during the conversation on remittances. Sadanand Sahoo and Feroz Khan of GRFDT facilitated the video recording and transcription of the conversation, which helped in the writing of this guest column. Surabhi Singh, formerly of the ICWA, had provided useful comments on an earlier draft. The author’s interview and the video message on remittances is available at https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=K27UJf9ifXk&t=1s

[i] UN Network on Migration, “Workstream 1: Development of a proposed limited set of indicators to review progress related to GCM implementation” https://migrationnetwork.un.org/sites/g/files/tmzbdl416/files/resources_files/Workstream%201%20-%20Discussion%20note%20final%20.pdf