Indian Council of World Affairs

Sapru House, New Delhi'The Changing Contours of Great Power Politics in West Africa'

In 2021-22, two significant developments occurred involving Russia and China in West Africa. First development was the leaked news reports about the possibility of the Chinese naval base in Equatorial Guinea. Equatorial Guinea is a small but strategically located country, with a population of about 1.4 million, along the Gulf of Guinea. The Chinese naval base in the Gulf of Guinea, first in the Atlantic Ocean but second in Africa, would have been a direct challenge for the American dominance of the Atlantic Ocean. Equatorial Guinea has received massive investments from China (to the tune of $ 2 billion) and is a participant in the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI).[1] The likely Chinese base directly facing the American mainland alarmed Washington sufficiently and forced it into an urgent action. United States (US) dispatched senior officials to visit Equatorial Guinea and persuade it from allowing the Chinese base.[2] For now, although the US has managed to thwart the Chinese ambitions in the Gulf of Guinea, it points to the growing influence and strategic presence of Beijing in the geopolitics of West Africa and the Gulf of Guinea.

The second important development was Russia’s dramatic entry into West African geopolitics. Russia was invited by the military junta of Mali to send private military contractors (PMC) of the Wagner group to support the fight against the Islamist rebels. Since 2012, French military had been engaged in the anti-terror fight, known as Operation Barkhane, in the semi-arid Sahel region. However, despite the years of military operations, insurgency in northern Mali and in the wider Sahel region had not abated. If anything, the challenge had only aggravated. Besides, in 2020, the Malian military overthrew the civilian government and took over power. The military junta was unhappy about the pro-democracy, anti-coup position taken by France and other Western countries. In a setback to the French and European interests in the region, military junta decided to kick out the French military from Mali.[3]

These two developments indicate that in the last few years, West Africa and the Gulf of Guinea region is undergoing geopolitical churning and the familiar patterns of great power politics are shifting. There are three clear trends in operation: first, the traditional, Western great powers are retreating from West Africa. France has been asked to leave Mali and Burkina Faso. Second, new, non-Western great powers are finding it easier to enter into the regions that were historically dominated by the West. Russia and China have managed to enter the West Africa in a major way. Russian presence is primarily in the domain of security and resource extraction. China is an important economic and investment partner for West Africa and has now demonstrated its willingness to expand its military presence in the region. Turkey, with the export of TB-2 drones and other military supplies, is also emerging as an important player in the regional security landscape whereas India too is a steadily expanding its presence in the region. Finally, the apparent geopolitical churn is bestowing West African countries with a degree of bargaining power. The stability as it existed for decades even after the decolonization from France has given way to an uncertain and volatile future. In some ways, however, the instability has been leveraged by the regional countries for their own benefit. They are making choices that are contributing to the churn and are trying to extract the best deal possible from the willing, new as well as old partners. Sensing this shift, the traditional great powers are making efforts to engage with the region. To underscore the importance of West Africa, the latest visit to Africa by US Vice President Kamala Harris began in Ghana.[4]

In this context, this article considers the evolving great power politics in West African geopolitics.

France and Europe: Changing Posture and New Partnerships

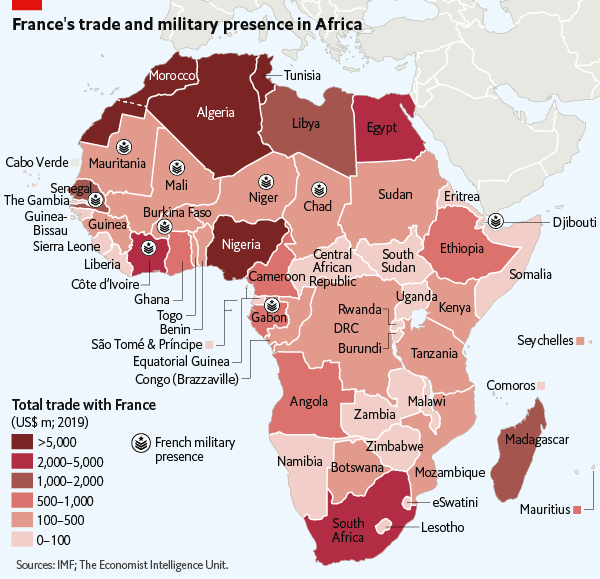

Historically, strategically, and culturally, France remains the most important player in the geopolitics of West Africa. The shifts or the continuities in the regional geopolitics are seen in the context of French actions or reactions to the developments within the region. France was the foremost colonial power in West Africa and looms large over the region even after the decolonization. The deep political, economic, military, and cultural links between France and West-Central Africa has shaped the strategic trajectory of the region. In the last few years, though, there has been a growing backlash against the overwhelming presence of France in West Africa and Paris has been trying to reshape the terms of engagement with the region. The ejection of France from Mali and Burkina Faso and the openly hostile attitude shown by these two governments is a sign of things to come for France in Africa. To make matters worse, these governments have engaged Russia, with whom France and Europe are locked in a spiral of confrontation over the Russia-Ukraine war. As the attitudes in Africa are shifting, France is forced to make changes to its strategic presence and posture as well. The latest speech unveiling a new Africa strategy by French President Emmanuel Macron has to be seen in this context.

In the last week of February, French President Emmanuel Macron embarked on his 18th visit to Africa. Before his visit began, he delivered a speech that aimed at resetting the France-Africa relationship. The speech was starkly different in its tone and tenor. In view of the deeply entrenched resentment in the region against the French military presence, economic domination and support for unsavoury political players including for the corrupt and autocratic regimes, Macron struck a note of humbleness. He maintained that ‘Africa is no longer France’s private preserve, that France has duties, interests, friendships to build, maintain, strengthen, to pursue solid policies’.[5] Macron spoke of building a ‘new, balanced, reciprocal and responsible relationship’ with Africa and asked the French elite to ‘show deep humility towards what is happening on the African continent’.[6] He went into granular details like ‘CEOs must travel to Africa when a major contract is agreed’.[7]

As security challenges intensify in the region, Macron argued that ‘our model must not be that of military bases as they exist today. In the future, our presence will be within bases, schools and academies which will be co-administered by French staff who will remain in place, but in a reduced capacity, and African staff who can also host other partners under their own conditions should they so wish’.[8] How the French defence establishment responds to such a change will be interesting to watch. For co-managing the military bases and seeking the best possible support from France, Macron argued that Africa should ‘very clearly set out their military and security needs’.[9] Based on it, France will increase ‘training, support, and equipment provision to the highest possible levels. In this way, this partnership will enable us to rebuild a model of proximity and interconnection between our armies, reflected in increased efforts from France in terms of training and equipment’.[10]

The new approach to the security relationship means France will co-manage military bases in Senegal, Ivory Coast and Gabon. The base in Ivory Coast is ideal for training for other West African militaries. However, the base in Djibouti in East Africa will remain exclusively French.[11] Interestingly, Macron observed that it was in ‘our interests to act collectively with our European allies and position Europe as a partner of reference on major defence and security issues. That is at the very core of what we will do beyond the pivot’.[12] For a long time, France guarded West Africa as its exclusive sphere of influence, even preventing its Western friends from entering the region in a big way. Therefore, the call to work with other European countries is a recognition of the strategic challenge posed by the new players as also an acknowledgement of the limits of French power.

French Presence in Africa

(Image Source: https://twitter.com/theeiu_africa/status/1326579827843985410)

The changing priorities of France and the need to reset its Africa policy has been driven by the desire to maintain French influence in the rapidly changing Africa. Moreover, the shifts in geopolitics after the Russia-Ukraine War has also been a key shaping factor. European countries that were excessively dependent on Russian energy exports are seeking alternative suppliers. West Africa might help Europe to diversify its energy suppliers. Therefore, in May 2022, German chancellor Olaf Scholz paid a visit to Senegal and Niger to pursue energy deals in the renewable and gas sector. Senegal is rich in gas resources and hopes to emerge as a major gas exporter for Europe. Senegalese President Macky Sall, who held the chairmanship of the African Union, was also invited by Germany to attend the G-7 summit.[13]

Meanwhile, just like France, Italy and Germany too had pulled out its troops from Mali. Troops have been re-deployed to Niger. Sweden and Denmark too decided to leave Mali in 2022. These pull-outs provided a major setback to the French efforts to 'Europeanize' the anti-terror operations in Sahel. In fact, at one point of time, European countries had deployed 1,100 troops as part of the European Training Mission (EUTM) in Mali. Furthermore, under the United Nations (UN) peacekeeping operation MINUSMA, 23 EU countries had deployed 1600 troops.[14] Therefore, Operation Takuba became known as ‘an unprecedented coalition of European special forces whose mission was to advise, assist, and accompany Malian armed forces in counterterrorism missions’.[15] In the vacuum left by the European departure, Russia seemed to easily find a way in.

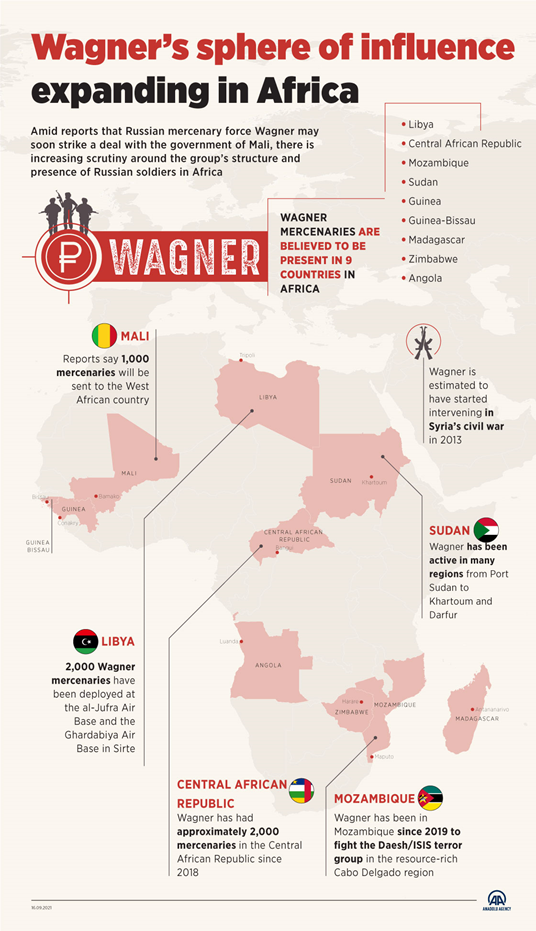

The Growing Presence of Russia

In the last few years, Russia has emerged as a key strategic partner for Africa. The most visible Russian presence, obviously, is in Mali and the Central African Republic (CAR). In 2017, Russia sent the Wagner military contractors to CAR and propped up the regime.[16] Similar playbook has now been repeated in Mali. In the case of Mali, Russian presence has been a major bone of contention between Paris and Moscow. The Malian military junta invited Russia’s Wagner group contractors in its fight against the Islamist rebels. In return, it agreed to provide mining contracts for extraction of gold. The Wagner group, which is founded by Yevgeny Prigozhin, who is believed to be close to the Kremlin, has been deployed across Africa including in Mozambique, Sudan, Madagascar, and Libya. CAR and Mali are seen as its successes whereas it had not succeeded in Mozambique against the rebels in Cabo Delgado.[17]

However, although the Wagner group has had an easy entry in Mali, its performance remains to be seen. In 2022, Wagner group was also sent to fight in Ukraine and the battle for the city of Bakhmut became a focus of their operations. However, months of fierce fighting has not resulted in the capture of Bakhmut. Ukrainian forces are still fighting and as per reports, the very public involvement of Wagner group has caused discomfort in the Russian defence establishment. There are indications that Wagner will reduce its focus in the war in Ukraine and train its attention back to Africa.[18]

Russian presence in Africa is not only about expanding security links, mostly at the cost of the Western presence, and acquiring lucrative mining contracts. Russia has no problems engaging with the military juntas or autocratic regimes of any type. In that way, its engagement in West Africa is regime neutral. Russia’s presence is welcomed by Mali and Burkina Faso, the two countries that had seen military coups. Unlike France and other Western countries, Russia has no baggage of colonialism and exploitation in Africa. Russia’s permanent membership of the United Nations Security Council (UNSC) and military-technological capabilities add another dimension to Moscow’s attractiveness in Africa.

Wagner Group in Africa

(Image Source: https://www.aa.com.tr/en/info/infographic/24909)

In the ongoing Russia-Ukraine war, Russia has engaged Africa far more effectively to drum up support for itself. Russian foreign minister Sergey Lavrov visited Africa twice in a span of a month and successfully managed to deepen support for Russia.[19] It is clearly visible in the UN voting patterns of African countries. It helped that in the past, Soviet Russia had supported many African countries in their national liberation struggles. Russia is building on this past and has managed to market its version of the war in Ukraine. In many countries, anti-Western feelings run high and there exists a natural sympathy for Russia.[20] Moreover, Russia also supports Africa in its quest for food security through the export of food and fertilizers.[21] In addition, technological and military assistance that might come from Russia is another attraction for the African states.

The growing Russian presence in West Africa has another dimension -- cyber. As per reports, Russia has successfully run disinformation campaigns against France in West Africa. As per Digital Forensic Research Lab, ‘a network of Facebook pages promoting pro-Russian and anti-French narratives drummed up support for Wagner Group mercenaries prior to the official arrival of the private military group in Mali’.[22] Interestingly, these pages ‘mobilized support for the postponement of democratic elections following a successful coup in May 2021, Mali’s second in less than a year’.[23] However, ‘the French-Russian proxy war by social media is not novel in Africa: in December 2020, Facebook removed a French network of 84 accounts, six pages and nine groups that targeted Mali with anti-Russian messages and promoted military interventions in the region in which France participated’.[24] With the French withdrawal and the increasingly entrenched Russian presence, these cyber disinformation campaigns as well as diplomatic manoeuvrings are likely to intensify even further.

China: Slow but steady

Just like Russia, China’s engagement with West Africa is expanding steadily. In the last two decades, China has been an important player in the oil industries of Nigeria, Angola, Benin, and Guinea-Bissau. It is building a 1980-km pipeline from Niger to Benin.[25] Moreover, in 2021, the Forum on China Africa Cooperation (FOCAC) took place in Senegal. It was held for the first time in a West African country.

China’s ambitions to expand its strategic presence in West Africa were evident when it sought to establish a military base at the port of Bata in West African waters by engaging Equatorial Guinea. The base would have expanded the strategic naval presence of China. During the 2014-2019, China engaged Gulf of Guinea countries for military exchanges 39 times.[26] Last year, in a webinar on the maritime security in the Gulf of Guinea, China’s People’s Liberation Army Navy commander Admiral Dong Jun asserted that ‘we are willing to increase the support in personnel training and other areas, provide assistance in information sharing and maritime rescue, carry out regular exchange of ship visits and joint training and exercises with relevant countries, and expand practical cooperation in the areas of exchange between military academies, medical services and hydrographic surveys’.[27] China's desire and intention to expand military presence in the Gulf of Guinea is clear.

Location of China’s likely naval base in Equatorial Guinea

(Image Source: https://areteafrica.com/2022/05/03/chinese-naval-base-in-guinea-its-implications/)

Apart from the piracy in the Gulf of Guinea, the instability in the Sahel region and the retreat of the Western powers opens up opportunities for the further expansion of Chinese military presence, primarily in the form of training as well as defence exports. West African countries like Nigeria and Cameroon are important customers of Chinese weapons systems. Nigeria also faces the challenge of Islamist insurgency in the North and has purchased unmanned aerial vehicles and armoured vehicles from China.[28] Moreover, Ghana’s security links with China are burgeoning in the domain of training and infrastructure building. China has donated four patrol boats and 100 military vehicles to Ghana.[29] However, despite the growing economic and military presence, China is yet to emerge as a major strategic player in West Africa. The rapidly evolving strategic landscape including the trajectory of Russia-Ukraine war and the ability or inability of Russia to concentrate in Africa may perhaps open up further opportunities for China.

Interestingly, the stringent Western sanctions on Russia and the reluctance by the Western countries to supply necessary arms and equipment will perhaps force many African countries, including in West Africa, to seek weapons from China. Compared with the Western weapons, Chinese arms are cheaper. For example, the US-made MQ-9 Reaper drone costs about $ 30 million whereas the Chinese made Wing Loong II costs about $ 1-2 million.[30] How China markets its weapons and can West African countries look to China for military support remains to be seen. Meanwhile, China’s growing interest in West Africa can be gauged from the fact that as the new foreign minister Qin Gang made his customary trip to Africa in January 2023, he visited two West African countries: Benin and Gabon.

In the context of intensifying strategic rivalries between US and France on the one hand and Russia and China on the other, West Africa is set to emerge as a key battleground for influence.

Turkey

Apart from the US, France, China, and Russia, Turkey is another key strategic player in West African geopolitics. Turkish presence in the region is growing, primarily in the domain of security. In 2020, Turkey signed agreements for defence cooperation with Niger and Nigeria. Next year, in November 2021, Niger decided to purchase highly effective TB-2 Turkish drones. In view of the growing threat of Islamist insurgency and their spreading reach, Togo too purchased TB-2 drones. For both Niger, and Togo, ‘the supply partnership with Turkey is also politically useful, reducing their public reliance on close security partnerships with France, the former colonial power, about which a significant strand of domestic opinion remains uneasy’.[31] Turkey is also a key military partner for West Africa in the education and training of military personnel.

India

India’s engagement with the West and Central Africa is expanding steadily. India has been a key player in the domain of energy security, development partnership, education, and training. India now operates diplomatic missions in 20 out of 25 countries located in West and Central Africa.[32] Traditionally, Nigeria and Ghana enjoyed close ties with India with Nigeria being a one of the largest oil suppliers. Moreover, Indian navy has begun to regularly mark its presence via port visits and joint naval exercises in the Gulf of Guinea. Last year, Indian navy’s INS Tarkash was deployed for the first time in the West African waters including in the Gulf of Guinea for anti-piracy deployments. It conducted joint naval exercises with the Nigerian navy as well as paid port visits to four countries: Dakar in Senegal, Lome in Togo, Lagos in Nigeria and Port Gentil in Gabon.[33]

Moreover, underlining the importance of West Africa, India has invited Nigeria as one of the guest countries to this year’s G-20 summit whereas the energy minister of Equatorial Guinea spoke in the Voice of Global South Summit organized in January.[34] In the India-Africa Defence Dialogue of 2022, India underscored its support to Africa to fight the challenges of conflict, terrorism, and violent extremism. It is particularly relevant in the context of the terrorism in Sahel. India is engaging African countries including those in West Africa for expanding defence exports.[35] Military training under the Indian Technical and Economic Co-operation (ITEC) program is also a key component of India’s engagement with the region.

Why is West Africa diversifying away from France and the West?

The above discussion begs a question: why West African countries engage with newer partners and are ditching their traditional partners? There are three possible explanations: first and foremost is the growing bitterness against the former colonial power – France. For many, the French domination of West Africa has not yielded tangible gains to the extent that many of these countries hoped. For example, from the Malian perspective, despite the decade-long French intervention in the Sahel, the threat of Islamist insurgency has not waned. In fact, the threat has worsened and in response, French military presence has expanded. Moreover, for decades, France continued to maintain unequal and paternalistic relations with these countries. French leaders in the past too spoke of resetting Franco-African ties but the structural basis of the relationship, close monetary, economic, political and military links, which greatly favours France, did not change.[36] Therefore, there is a resentment in many countries against the French presence. It is fuelled even further by the disinformation campaigns run on social media by Russia.

The second reason behind the West African desire to move away from France and Europe is that new partners like China, Russia and Turkey are willing to engage with these countries and are offering tangible economic and military assistance. They do not lecture these countries about democracy, human rights, and rule of law. China has been a key economic partner for many energy-rich West and Central African countries. It is now expanding its presence in the military sphere as well. Russia and Turkey are active in the domain of security.

France too did not care about the nature of regimes in West and Central Africa. Yet, it did oppose the military coups in Mali and Burkina Faso. The incoming, military-led regimes sensed an opportunity in the deteriorating relations between the West and Russia and sought to invite Russia in their fight against the Islamist rebels. The Russia-Ukraine War has sharpened the strategic rivalries between the West and Russia and Africa has emerged as a key battleground for influence.[37] This has allowed West Africa to make their own strategic choices.

This leads us to the third possible explanation about the desire of West African countries to move away from France and the West. The third and final factor that is driving West Africa’s foreign policy choices is that in an age of heightened global tensions, these countries have attained greater agency. The growing power of China and Turkey along with the return of Russia to Africa is providing West Africa with a set of choices that it lacked for many years. The apparent limits of French and European powers in Africa along with the baggage of history of colonialism and post-colonial domination has made it even more difficult for the West to retain its influence in the region. The Western narrative regarding the Russia-Ukraine War has not found many takers in Africa. If anything, African countries have been sympathetic about the Russian security concerns and many of them have continued to deepen ties with Russia in spite of the Western sanctions.

Conclusion

The great power politics in West Africa and the Gulf of Guinea region is undergoing changes. France and other European powers are finding it difficult to retain their influence in the region. Russia presents the most important challenge for European influence. China too is eyeing the region for expanding its military and economic presence. The possibility of a Chinese naval base in the Gulf of Guinea remains real. Meanwhile, French exit from Mali and Burkina Faso and the end of the French-led military operations in these two countries have demonstrated the limits of French power as well as the feeling of resentment in the region. Therefore, France has shifted its narrative. It has launched a new strategy for Africa and is deploying the language of ‘humility’ and ‘new and balanced partnerships’ to signal its willingness for resetting France-Africa ties. It has re-deployed troops to Niger and is making efforts to stay engaged and revive its influence in the region. For the French self-image of a great power as well as its global presence and strategic calculations, influence in West and Central Africa is a key component. The structural and historical advantages that France enjoys in the region will be leveraged by Paris to stage a comeback. The question is not about ‘if France can make a comeback’ but that of ‘when’ and ‘how’. For now, France is finding it tough to retain its influence in West-Central Africa. But it would be prudent to not count France out of the geopolitics of West Africa and the Gulf of Guinea region as yet.

*****

(Author Bio: Sankalp Gurjar is an Assistant Professor at the Department of Geopolitics and International Relations, Manipal Academy of Higher Education, Udupi, India. Prior to that, he worked as a Research Fellow with the Indian Council of World Affairs, New Delhi. He writes on Great Power Politics, Geopolitics of the Indian Ocean region and Indo-Pacific security.)

References:

[1] Reuters, ‘China agrees $2-billion infrastructure deal with Equatorial Guinea’, April 29, 2015. Available at: https://www.reuters.com/article/us-china-equatorial-idUSKBN0NK16I20150429 (Accessed on April 6, 2023).

[2] Michael M. Phillips, ‘China Seeks First Military Base on Africa’s Atlantic Coast, U.S. Intelligence Finds’, The Wall Street Journal, December 5, 2021. Available at: https://www.wsj.com/articles/china-seeks-first-military-base-on-africas-atlantic-coast-u-s-intelligence-finds-11638726327 (Accessed on April 6, 2023).

[3] Catrina Doxsee , Jared Thompson , and Marielle Harris, ‘The End of Operation Barkhane and the Future of Counterterrorism in Mali’, CSIS, March 2, 2022. Available at: https://www.csis.org/analysis/end-operation-barkhane-and-future-counterterrorism-mali (Accessed on April 6, 2023).

[4] Anne Soy, ‘Kamala Harris Africa trip: Can US charm offensive woo continent from China?’, BBC News, March 26, 2023. Available at: https://www.bbc.com/news/world-africa-65062976 (Accessed on April 6, 2023).

[5] Emmanuel Macron, ‘Address by the President of the Republic before his visit to Central Africa’, France in the United States, February 27, 2023. Available at: https://franceintheus.org/spip.php?article11212 (Accessed on April 6, 2023).

[6] Ibid

[7] Ibid

[8] Ibid

[9] Ibid

[10] Ibid

[11] Paul Melly, ‘Emmanuel Macron's mission to counter Russia in Africa’, BBC News, March 4, 2023. Available at: https://www.bbc.com/news/world-africa-64822485 (Accessed on April 6, 2023).

[12] Emmanuel Macron, ‘Address by the President of the Republic before his visit to Central Africa’, France in the United States, February 27, 2023. Available at: https://franceintheus.org/spip.php?article11212 (Accessed on April 6, 2023).

[13] Reuters, ‘Germany is keen to pursue gas projects with Senegal, says Scholz on first African tour’, CNN, May 23, 2022. Available at: https://edition.cnn.com/2022/05/23/africa/olaf-scholz-african-tour-intl/index.html (Accessed on April 6, 2023).

[14] Marie Jourdain and Petr Tůma ‘As Europe withdraws from Mali, Russia gets the upper hand’, Atlantic Council, June 7, 2022. Available at: https://www.atlanticcouncil.org/blogs/new-atlanticist/as-europe-withdraws-from-mali-russia-gets-the-upper-hand/ (Accessed on April 6, 2023).

[15] Ibid

[16] Federica Saini Fasanotti, ‘Russia’s Wagner Group in Africa: Influence, commercial concessions, rights violations, and counterinsurgency failure’, Brookings Institution, February 8, 2022. Available at: https://www.brookings.edu/blog/order-from-chaos/2022/02/08/russias-wagner-group-in-africa-influence-commercial-concessions-rights-violations-and-counterinsurgency-failure/ (Accessed on April 6, 2023).

[17] Ibid

[18] Bloomberg, ‘Putin’s Mercenary Prigozhin Shifts Focus After Ukraine Setbacks’, March 23, 2023. Available at: https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2023-03-23/putin-s-mercenary-prigozhin-shifts-focus-after-ukraine-setbacks (Accessed on April 6, 2023).

[19] Vadim Zaytsev, 'What’s Behind Russia’s Charm Offensive in Africa?’ Carnegie Politika, February 17, 2023. Available at: https://carnegieendowment.org/politika/89067 (Accessed on April 6, 2023).

[20] The Economist, ‘Why Russia wins some sympathy in Africa and the Middle East’, March 12, 2022. Available at: https://www.economist.com/middle-east-and-africa/2022/03/12/why-russia-wins-some-sympathy-in-africa-and-the-middle-east (Accessed on April 6, 2023).

[21] Al Jazeera, ‘First shipment of Russian fertiliser en route to Africa’, November 30, 2022. Available at: https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2022/11/30/first-shipment-of-russian-fertiliser-en-route-to-africa (Accessed on April 6, 2023).

[22] Jean Le Roux, 'Pro-Russian Facebook assets in Mali coordinated support for Wagner Group, anti-democracy protests’, DFR Lab, February 17, 2022. Available at: https://medium.com/dfrlab/pro-russian-facebook-assets-in-mali-coordinated-support-for-wagner-group-anti-democracy-protests-2abaac4d87c4 (Accessed on April 6, 2023).

[23] Ibid

[24] Ibid

[25] Africa Oil Week, ‘Understanding Chinese investment in African oil and gas’, 2023. Available at: https://africa-oilweek.com/articles/understanding-chinese-investment-in-african-o (Accessed on April 6, 2023).

[26] Dipanjan Roy Choudhury, ‘Equatorial Guinea: New backdrop for Sino-US rivalry’, The Economic Times, March 21, 2022. Available at: https://economictimes.indiatimes.com/news/international/world-news/equatorial-guinea-new-backdrop-for-sino-us-rivalry/articleshow/90354940.cms?from=mdr (Accessed on April 6, 2023).

[27] China Military Online, ‘Navies of China, Gulf of Guinea countries eye maritime security cooperation’, May 27, 2022. Available at: http://eng.chinamil.com.cn/CHINA_209163/TopStories_209189/10158454.html (Accessed on April 6, 2023).

[28] Murtala Abdullahi, ‘Analysis: Russia sanctions could spur Chinese arms sales to Nigeria’, Al Jazeera, April 1, 2022. Available at: https://www.aljazeera.com/features/2022/4/1/ukraine-war-sanctions-could-boost-chinese-arms-supply-to-nigeria (Accessed on April 6, 2023).

[29] Ilaria Carrozza & Marie Sandnes, ‘China’s Engagement in West Africa: The Cases of Ghana and Senegal’, PRIO Policy Brief, 9. 2022, Oslo: PRIO.

[30] Murtala Abdullahi, ‘Analysis: Russia sanctions could spur Chinese arms sales to Nigeria’, Al Jazeera, April 1, 2022. Available at: https://www.aljazeera.com/features/2022/4/1/ukraine-war-sanctions-could-boost-chinese-arms-supply-to-nigeria (Accessed on April 6, 2023).

[31] Paul Melly, ‘Turkey's Bayraktar TB2 drone: Why African states are buying them’, BBC News, August 25, 2022. Available at: https://www.bbc.com/news/world-africa-62485325 (Accessed on April 6, 2023).

[32] Ministry of External Affairs, ‘Annual Report: 2022’, February 2023, pp: 112-113. Available at: https://mea.gov.in/Uploads/PublicationDocs/36286_MEA_Annual_Report_2022_English_web.pdf (Accessed on April 6, 2023).

[33] ANI, ‘INS Tarkash completes Gulf of Guinea anti-piracy deployment’, The Print, October 4, 2022. Available at: https://theprint.in/world/ins-tarkash-completes-gulf-of-guinea-anti-piracy-deployment/1154540/ (Accessed on April 6, 2023).

[34] Press Information Bureau, ‘Voice of Global South Summit’, January 13, 2023. Available at: https://pib.gov.in/PressReleasePage.aspx?PRID=1891153#:~:text=Hardeep%20S%20Puri%20addressed%20the,is%20affordable%2C%20accessible%20and%20sustainable. (Accessed on April 6, 2023).

[35] Press Information Bureau, ‘India-Africa Defence Dialogue held on the sidelines of DefExpo 2022 in Gandhinagar, Gujarat; paves way for strengthening of India-Africa defence relations’, October 18, 2022. Available at: https://pib.gov.in/PressReleasePage.aspx?PRID=1868820 (Accessed on April 6, 2022).

[36] Paul Taylor, ‘Macron’s Africa reset struggles to persuade’, Politico, March 13, 2023. Available at: https://www.politico.eu/article/france-emmanuel-macron-africa-reset-strategy-francafrique/ (Accessed on April 6, 2023).

[37] Akayla Gardner, ‘US Fights for Influence in Africa Where China, Russia Loom Large’, Bloomberg, March 24, 2023. Available at: https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2023-03-24/us-fights-for-influence-in-africa-where-china-russia-loom-large#xj4y7vzkg (Accessed on April 6, 2023).