Indian Council of World Affairs

Sapru House, New DelhiChina Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC)

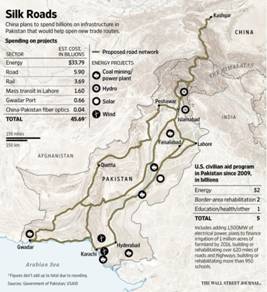

South Asia is recognised as a region that is marred by instability, economic underdevelopment and conflict. When avenues of cooperation leading to development are sought, naturally, it strengthens the prospects for a stronger and stable region. The recent visit of Chinese President Xi Jinping to Pakistan brought forth the hopes of such stability for Pakistan in the forthcoming years. The idea of developing a China Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC), which was visualised by Chinese Premier Li Keqiang during his visit to Pakistan on May 2013, found a proper shape in the present visit.1 The proposed economic corridor will connect the north-western Chinese province of Xinjiang with the Pakistani port of Gwadar through a network of roads measuring around 3000 kms (1,800 miles), providing Pakistan its much-needed economic infrastructure, especially power-generation plants.2

The China-Pakistan Economic Corridor is located where the Silk Road Economic Belt and the 21st Century Maritime Silk Road meet. It is, therefore, a major project of the "Belt and Road" initiative.3

Beijing is concerned that without economic development and stabilization, Pakistan and Afghanistan would undermine security on China’s northwest flank. The economic corridor also aims to help economically develop the predominantly Muslim northwest region of China by connecting it with Gwadar, a closer outlet than any Chinese coastal port.4

China has made commitments to provide around $46 billion in development deals, which is equivalent to roughly 20 per cent of Pakistan's annual GDP.5 In total, the economic corridor project aims to add some 17,000 megawatts of electricity generation at a cost of around $34 billion. The rest of the money will be spent on transport infrastructure, including upgrading the railway line between the port megacity of Karachi and the northwest city of Peshawar.6

The plan calls for the completion of all the projects by 2030.7 The economic corridor will shorten the route for China's energy imports from the Middle East by about 12,000 kms as well as link China's underdeveloped far-western region to Pakistan's Gwadar deep-sea port on the Arabian Sea via PoK through a massive and complex network of roads, railways, business zones, energy schemes and pipelines.8 Some $15.5bn worth of coal, wind, solar and hydro energy projects will come online by 2017 and add 10,400 megawatts of energy to Pakistan's national grid. A $44m optical fibre cable between the two countries is also due to be built.9

As some of the projects will cover areas falling in the disputed regions of Pakistan occupied Kashmir, there have been some reservations about the corridor from India. However, the Assistant Foreign Minister, Liu Jianchao made it clear to the media, when he stated, “The project between China and Pakistan does not concern the relevant dispute between India and Pakistan. So I do not think that the Indian side should be over concerned about that.”10 However, India has expressed reservations on the issue. When India embarked on the exploration of oil and gas in the South China Sea region, China had declared it as one of its “core areas”.

Chinese Investment Policy

Chinese policies on Asia range from projecting assertiveness on maritime issues, to challenging the post-war order in the Pacific, to spinning a web of win-win economic ties built from trade strength, which could make China the nucleus of regional integration.11 Xi Jinping’s speech defining a new “Maritime Silk Road” at the APEC summit in Bali in October 2013 made the leadership’s thinking clear and closed down space for speculation.12 Analysts have made it clear that the Chinese foreign policy from 2002, along with whatever determinants it carried forward from the Deng Xiaoping era, linking it with the changes that was brought in by Hu Jintao, centres around United States, some considering the US as a deus ex machina13 that must be examined in isolation, and others looking at it in the more benign context of globalisation and international interdependence.14 For China, foreign policy is subordinate to the domestic goals of maintaining internal stability and economic growth.15

Since the implementation of China’s “Go Global” initiative in 2001, the Chinese government has relaxed its foreign exchange controls, approval procedures, and investment restrictions. From 2003 onward, privately owned enterprises have been allowed to apply for permission to invest internationally.16 Since this time, Chinese ODI has rapidly expanded from less than US$ 3 billion in 2003 to more than US$ 70 billion in 2011.17 While state-owned enterprises continue to be the largest investors—mainly in petroleum, construction, telecommunications, and shipping—private companies, such as Lenovo have started to invest abroad.18

Although the majority of China’s ODI is directed toward Southeast Asia; since 2003, China has increased its diplomatic and economic focus on South Asia. It is difficult to discern whether China has geopolitical reasons for strengthening economic ties with South Asia. On the one hand, Chinese objectives could be strictly a function of export-led growth strategies and a desire to expand trade routes. On the other hand, ties with the region could be equally important for China to exercise diplomatic pressure and extend the reach of its military.19 Such a threat could have been overlooked if the Chinese military, especially the People’s Armed Police showed restraint while making border incursions in India.20 Border incursions have been repeatedly used by China to keep India on the defensive. Before every major bilateral visit, such incursions tend to take a serious dimension.21 China, in its recent policy formulations, has not stressed on dispute resolution, which makes a tacit statement that neighbours are meant to reciprocate by lowering the profile of their expectations and claims.22

Various analysts have tried to assess the manner in which Chinese aid and overseas projects function, as such statistics are not transparent as per the data provided by the Chinese. As per the White Paper that was issued by China in 2011, it was mentioned that China would help recipient countries strengthen their self-development capacity, enrich and improve their people’s livelihoods, and promote their economic growth and social progress. The purpose of the 2011 White Paper was to set out China’s foreign aid policy, and to provide information about China’s foreign aid mechanisms. As an extension of the 2011 White Paper, the White Paper II provides an overview of China’s foreign aid between 2010 and 2012, and elaborates China’s achievements in this regard during the three-year period. The data and statistics provided cover only aid figures from the Ministry of Commerce (MOFCOM) and concessional loans from the Exim Bank, and exclude official aid flows from other ministries (which also does not include contributions to international development agencies, such as the World Bank by the Ministry of Finance and the Ministry of Education).23 The aim of these grants, which at times are locked grants, is basically meant to build positive constituency about China’s rise and also provide employment opportunities to Chinese labour.

The Chinese Perspective

By investing heavily on the CPEC, China has made an attempt to fulfil multiple interests of its own. Energy and infrastructural projects of around $45.6 billion will be completed over the next six years, where Chinese companies will be able to operate the projects as profit-making entities. As per media reports, the Chinese state and its banks would lend to Chinese companies to carry out the work, thereby making it a commercial venture with direct impact on China's slackening economy.24

Though Pakistan is ill-famed of rampant official corruption, militancy, separatism, and political volatility, China has been making significant financial investments in the region. Though there have been three major incidents of Chinese nationals or officials being targeted inside Pakistani territory (one by Balochi insurgents 2004, and two by Pakistani Taliban 2008 and 2014), there have been stray incidents and attacks on developmental work in the region. One such attack on the Gwadar port, opposed by Balochi insurgents, culminated with the visit of the Chinese President.25 Developing this specific zone had a specific counter terrorist dimension to it. China has been significantly troubled by the East Turkestan Islamic Movement (ETIM), which was responsible for the death of hundreds of Chinese in the last two years.26 Developing the regions that fall within the ambit of the corridor, famed for underdevelopment and being the training camps of Uighur rebels near the borders of Pakistan and Afghanistan, might resolve the terrorist dimension in Xinjiang. China is also worried about violence from ethnic Uighurs in its mostly Muslim north-western Xinjiang region and fears that hard-line separatists could team up with Uighur militants fighting alongside members of Pakistan's Taliban.27

As the threat perception both by the Chinese and the Pakistani government has been found to be real, Pakistan will be providing a special security division comprising of 12,000-men strong army battalions and CAF (Civil Armed Forces) wings dedicated to protect the Pakistan-China economic projects. The division will be headed by a Major General and will be made up of nine army battalions and six CAF wings (Rangers and Frontier Corps).28 Training of the special force would partly be carried out at the newly set up National Counter-Terrorism Centre in Pabbi. The training regime will include security, counter-terrorism and intelligence drills.29

The projects also give China direct access to the Indian Ocean and beyond, marking a major advance in China's plans to boost its influence in Central and South Asia.30 As the world's biggest oil importer, energy security is a key concern for China. It gets a pipeline that stretches virtually from the Gulf to China, cutting out thousands of kilometres of ocean travel through Southeast Asia.31

In November 2014, Xi made a speech at the Chinese Communist Party’s Central Conference on Work Relating to Foreign Affairs. In the speech, the president laid out a seemingly new order in China’s diplomatic objectives. He spoke of prioritising the promotion of neighbourhood diplomacy over the management of relations with other major powers, which was moved away from his previous statement that he made in 2012 about forging better relations with United States, coining the term, a “new type of great power relations”. China must avoid falling into a Thucydides trap: a situation in which a rising power, in this case China, inspires fear in an established power, in this case the US, which eventually leads to open confrontation.32 China’s relations with the current superpower, the US, and its closest ally, Japan, cannot, for structural reasons, improve past a certain threshold. Therefore, China must focus its efforts where they can be the most effective: that is, it must work to improve its relations with its neighbours. The best strategy to sustain China’s rise is, thus, to develop its neighbourhood diplomacy. The new Silk Road projects will be the key to achieving this objective.33

Analysts have suggested Chinese decision makers to adopt a “two pronged approach”, where while establishing new great power relations with developed great powers, it should improve its relations with developing and neighbouring countries. This echoes the position of Li Yonghui, the director of the School of International Relations at Beijing Foreign Studies University, who said in late 2013 that rising powers need a friendly periphery, which he called a “strategic periphery belt”.34 Not only did China invest in the China Pakistan Economic Corridor, it has even plans to invest in the “Silk Road Economic Belt with Central Asia”, the “Maritime Silk Road with Southeast Asia”, and the “South Asia Economic Corridor” that would link China with Burma, Bangladesh, and India.

In his conversation with Prime Minister Modi, Li Keqiang, the Chinese Prime Minister expressed an interest in continuing to develop the Bangladesh-China-India-Myanmar (BCIM) economic corridor, one of many westward-looking economic plans promoted by Beijing. China also envisions India as a part of the new “Maritime Silk Road,” an ambitious oceanic trade route linking China and Europe via Southeast Asia, India, and Africa. On both land and sea, India is an important part of China’s vision for economic integration with western Asia and beyond. Beijing is optimistic that its vision will mesh well with Modi’s economic goals for India.35

The Maritime Silk Road is the most important of the three projects. The Silk Road Economic Belt in Central Asia is aimed at consolidating China’s “strategic rear” in a region where both economic development potential and traditional security threats are already low. But the Maritime Silk Road concerns the central area of China’s rise. If China is to counter the US’s regional influence, investment and involvement in Southeast Asia is more urgent and offers more strategic benefits than in Central Asia.36

The Pakistani Perspective

The major achievement of Pakistan is to rope in China in finding a fast and durable solution to the endemic energy crisis that has engulfed it. The proposed project would make an attempt to fix Pakistan’s dilapidated power infrastructure—an urgent and long-unsolved problem that, experts say, shaves at least two per cent off the country’s gross domestic product each year.37 The project will add 10,400 Megawatts to Pakistan's energy grid through coal, nuclear and renewable energy projects.38

Pakistan and China signed on April 20 agreements worth US$ 28 billion to immediately kick-start ‘early harvest’ projects under the PCEC. The US$ 28 bn financing agreements will immediately enter the implementation phase because necessary processes have already been completed. These include: 1000MW solar power park in Punjab; 870MW Suki Kanari (Khyber Pakhtunkhwa) hydropower project; 720MW Karot (AJK) hydropower project; three wind power projects at Thatta of United Energy Pakistan (100MW), Sachal (50MW) and Hydro-China (50MW); Chinese government’s concessional loans for the second phase upgradation of Karakorum Highway (Havelian to Thakot); Karachi-Lahore Motorway (Multan to Sukkur), Gwadar Port east-bay expressway project and Gwadar international airport; provision of material for tackling climate change; projects in the Gwadar Port region and establishment of China-Pakistan Joint Cotton Biotech Laboratory and China-Pakistan Joint Marine Research Centre.39

An agreement for cooperation between the State Administration of Press, Publication, Radio, Films and Television of China and Pakistan’s Ministry of Information, Broadcasting and National Heritage and a tripartite agreement between China Central Television and PTV and Pakistan Television Foundation for rebroadcasting of CCTV-NEWS/CCTV-9 Documentary in Pakistan were also signed.40 Protocol agreements were signed on the establishment of sister-cities relationship between Chengdu (in China’s Sichuan province) and Lahore; Zhuhai (Guangdong province) and Gwadar and Karamay (Xinjiang Uyghur) and Gwadar.41

Another agreement was signed on the Gwadar-Nawabshah LNG terminal and pipeline project and commercial contract and agreements on financing for Lahore Orange Line Metro Train project, Port Qasim 2x660MW (1320MW) coal-fired power plant, Jhimpir wind power project, Thar Block II 3.8 million tons coal production per annum and Thar Block II 2x330MW (660MW) coal-fired power project.42

A financing cooperation agreement was signed by China Development Corporation and Habib Bank Limited for the implementation of the PCEC. An MoU between Wapda, PPIB and China Three Gorges Corporation (CTG) for cooperation in development of hydropower projects and Silk Road Fund on the development of private hydropower projects were also signed.43

A financing facility agreement between Industrial and Commercial Bank of China (ICBC), PCC of China and HDPPL for Dawood wind power project and a framework agreement on financial services corporation between ICBC and HBL for promoting Chinese investments and development of industrial parks in Pakistan were signed.44

Balochistan has remained an area that has been contentious to the Pakistani government, which is the base for many extremist and secessionist groups. The major chunk of the corridor will fall in that region, which will change the demography of the region, making it more economically viable, stable and sustainable. Pakistani Prime Minister Nawaz Sharif has also stated that this corridor would transform Pakistan into a regional hub of economic activities.45

Chinese Investments – The Challenges Involved

- There have been apprehensions as well about the rate of success and quality maintenance that Chinese investments have brought about. As per two researchers affiliated with a Chinese state agency, the delivery rate of completed capital projects, which was 74-79 per cent in the late 1990s, has now fallen below 60 per cent. This implies that nearly 40 per cent of Chinese investment projects are either not finished on time or not completed at all.46

The even more alarming figure, which made headlines around the world, is that ineffective investment has cost China US$ 10.8 trillion since 1997. Sixty-two per cent of the wasteful investment—US$ 6.8 trillion—was made after 2009, when China went on an investment binge to stimulate its economy. The Chinese government and state-owned enterprises invest US$ 2.3 trillion a year in infrastructure and factories (43 per cent of the country’s total investment). Since government-funded investments are driven by political decisions, these investments are more likely to fall victim to waste and corruption.47

Edwin Lee, a lawyer and overseas investment consultant, while speaking to China Dialogue, mentioned, “The main aspect of Chinese overseas investment today that makes host nations nervous is too strong a focus on obtaining resources. The issues reported in the media – pollution, poor community relations, a failure to use local labour – are all results of Chinese companies taking an unsuitable approach.”48 He stated that when China invests in the developed world, like the US or Australia, it makes significant endeavours to follow the local legal structure and employs expert legal counsel, so as not to break any local law, but that is usually not followed when China invests in the developing world. Similarly, China has significantly developed or seeks to develop access points towards the Gulf, or the Indian Ocean trade route or seeks to gain access to raw materials from the host country. If you have an industrial chain in place, then cutting off your supply of raw materials means that employees in the processing and manufacturing operations lose their jobs, which means that the government will be more cautious.49

As per a discussion by a senior analyst and diplomat, the manner in which Chinese foreign investments are put to use, it seriously contradicts the basic theme of the White Papers issued by China in 2011 and 2014. Especially, in the massive investments made by China in its neighbouring nations including Africa in the last three to four decades, bilateral investment deals have been usually opaque in nature. In the various infrastructural development projects, local indigenous markets have been fully overlooked, stressing entirely on Chinese services and logistics, where even the labour is brought in from Chinese mainland, salaries paid to their families directly, sustenance of the labourers being provided directly by China, bringing all material and manufacturing material from the mainland, which would be paid from the investment package. In that way, though it seems that a huge investment is made, not a single yuan leaves China during the entire developmental process.50 - The alleged neo-imperialist role of China has also been discussed by analysts when China has been involved in Latin America, Africa as well as in Afghanistan and Pakistan. In 2006, when Afghan President Karzai opened Afghanistan’s vast mineral deposits, and other natural resources to foreign investment, China took full advantage of this economic windfall. While the United States and ISAF provided for the security of the Afghan people, the Chinese were conducting economic imperialism. China outmanoeuvred companies from the United States, Canada, and Russia to gain control of the Aynak copper field in Logar province, estimated to be the world’s largest shallow reserve with 240 million tons of ore. China’s Metallurgical Group Corporation, or MCC, outbid the other countries at US$ 3.9 billion, but this is only part of the story.51 The PRC, which coincidently owns 44 per cent of MCC, tied the contract award directly to extensive development projects slated for Chinese companies.52 This is a competitive advantage that companies from other countries do not enjoy.53 It has even been stated by analysts that in Pakistan, to control the East Turkestan Islamic Movement, Chinese leadership sought basing rights in the FATA in order to facilitate military operations against these terrorists.54 But with the present agreement in place, it would facilitate the Chinese leadership to draw up a larger game plan that would involve not only controlling the anti-Chinese activities carried out from mainland Pakistan, but also gaining access to the Gulf as well as the Indian Ocean, which also strengthens the argument for those, who are in favour of the Chinese encirclement theory of India.

- China has invested significantly in Pakistan Occupied Kashmir (PoK), which remains a disputed territory between India and Pakistan, especially in developing the Karakoram Highway, involving several thousand Chinese personnel belonging to the construction corps of the People's Liberation Army (PLA).55 A large section of the China Pakistan Economic Corridor also lies through the areas of Gilgit-Baltistan in PoK, which some analysts in India have protested.56 As China does not entertain any sort of development work in Arunachal Pradesh, as analysts have pointed out that China “has been against Asian Development Bank funds being given to developmental projects in Arunachal Pradesh which it considers disputed; Beijing has also objected to Japanese funds being utilised for such projects in Arunachal Pradesh,”57 it shows the amount of double standards China maintains as far as the PoK and disputed territories in Arunachal Pradesh is concerned. China even protests the Indian Prime Minister visiting Arunachal Pradesh, which remains an integral part of India.58

India has been playing a significant role in strengthening its position amongst the South Asian nations. Its positive positioning during the swearing-in ceremony of the Prime Minister; the role played by Modi in Kathmandu during the SAARC Summit; the multiple visits the leadership made to Bangladesh, Bhutan, Nepal and Sri Lanka; the closeness with Japan and the United States; and the frequent dialogues with and visits to China, all these have brought significant dynamism to Indian strategic and regional economic position. Some analysts have stated that openly supporting the Silk Route as proposed by China would jeopardise India’s sovereign status in some of the territories that China claims to be its own, especially in the Aksai Chin region and in Arunachal Pradesh. India should strengthen and work whole heartedly in parallel projects that it has launched like that of the “Cotton Route” project along the North South Corridor, as well as Project Mausam, a regional initiative to revive its ancient maritime routes and cultural linkages with countries in the extended neighbourhood.59 India should stress more on developing the Chabahar port as “in the absence of transit through Pakistan, Iran is India's gateway to Afghanistan, Central Asia, and Russia and beyond, and the Chabahar port is the key element in that”.60 Strengthening Chabahar should act as a strong initiative towards countering a lopsided development process that might undermine the fragile balance that South Asia hangs on. Such projects need to be strengthened as it would bolster the development activity in the true sense, rather than culminating in resource drainage by a bigger power that would lead to more deprivation and exploitation in the guise of aid and assistance.

*The Author is Research Fellow at the Indian Council of World Affairs, New Delhi.

End Notes

1 “Chinese Premier Hopes for More Fruits in Friendship with Pakistan” (2013), Xinhuanet, May 24, http://news.xinhuanet.com/english/china/2013-05/24/c_124755924.htm

2 Saeed Shah, “China’s Xi Jinping Launches Investment Deal in Pakistan”, The Wall Street Journal, April 20, 2015, http://www.wsj.com/articles/chinas-xi-jinping-set-to-launch-investment-deal-in-pakistan-1429533767

3 Foreign Ministry Spokesperson Hong Lei's Regular Press Conference on April 20, 2015, Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the People’s Republic of China, http://www.fmprc.gov.cn/mfa_eng/xwfw_665399/s2510_665401/t1256093.shtml

4 Saeed Shah, “China’s Xi Jinping Launches Investment Deal in Pakistan”, op. cit.

5 Andrew Stevens (2015), “Pakistan Lands $46 Billion Investment from China”, CNN, Money, April 20, http://money.cnn.com/2015/04/20/news/economy/pakistan-china-aid-infrastucture/

6 Saeed Shah, China’s Xi Jinping Launches Investment Deal in Pakistan, op. cit.

7 Ibid.

8 “China and Pakistan Just did Something that will Anger India”, RediffNews, April 20, 2015, http://www.rediff.com/news/report/china-and-pakistan-just-did-something-will-anger-india/20150420.htm

9 M Ilyas Khan, “China's Xi Jinping Agrees $46bn Superhighway to Pakistan”, BBC News, Asia, April 20, 2015, http://www.bbc.com/news/world-asia-32377088

10 “China, Pakistan Ink CPEC, 50 Other Deals on Xi Jinping's Historic Visit” (2015), The Economic Times, April 20, 2015, http://economictimes.indiatimes.com/news/international/world-news/china-pakistan-ink-cpec-50-other-deals-on-xi-jinpings-historic-visit/articleshow/46990263.cms

11 François Godement, “China’s Neighbourhood Policy”, European Council on Foreign Relations, Asia Centre, China Analysis, February, 2014, http://www.ecfr.eu/page/-/China_Analysis_China_s_Neighbourhood_Policy_February2014.pdf

12 Ibid.

13 The term ‘deus ex machina’ usually connotes when ‘a seemingly unsolvable problem is suddenly and abruptly resolved by the contrived and unexpected intervention of some new event, character, ability or object.’ And it also needs to be understood that US has been playing a significant role in world politics since World War II, considering US as deus ex machina was analysed in the perspective of China only.

14 François Godement, “China’s Neighbourhood Policy”,op. cit.

15 Marianna Brungs, “China and its Regional Role”, Short Term Policy Brief 77, Europe China Research and Advice Network (ECRAN), 2010/256-524, December, 2013, p. 4, http://eeas.europa.eu/china/docs/division_ecran/ecran_is99_paper_77_china_and_its_regional_role_marianna_brungs_en.pdf

16 Buckley, Peter J., Adam R. Cross, Hui Tan, Liu Xin, and Hinrich Voss, “Historic and Emergent Trends in Chinese Outward Direct Investment”, Management International Review, vol. 48, no. 6, (2008), pp. 715-748

17 China Commerce Yearbook (2012), Beijing: China Commerce and Trade Press; China Commerce Yearbook (2010), Beijing: China Commerce and Trade Press

18 Morck, Randall, Bernard Yeung, and Minyuan Zhao, “Perspectives on China’s Outward Foreign Direct Investment”, Journal of International Business Studies, vol. 39, no. 3 (2008), pp. 337-350; Emily Brunjes, Nicholas Levine, Miriam Palmer and Addison Smith, “China’s Increased Trade and Investment in South Asia (Spoiler Alert: It’s The Economy)”, The Robert M. La Follette School of Public Affairs, University of Wisconsin-Madison, Workshop in International Public Affairs, Spring (2013), p. 2, https://www.lafollette.wisc.edu/images/publications/workshops/2013-China.pdf

19 Emily Brunjes, Nicholas Levine, Miriam Palmer and Addison Smith, “China’s Increased Trade and Investment in South Asia (Spoiler Alert: It’s The Economy)”, The Robert M. La Follette School of Public Affairs, University of Wisconsin-Madison, Workshop in International Public Affairs, Spring (2013), p. 2, https://www.lafollette.wisc.edu/images/publications/workshops/2013-China.pdf

20 Ibid.

21 Harsh V Pant, “Why Border Stand-offs Between India and China are Increasing”, BBC, News, September 26, 2014, http://www.bbc.com/news/world-asia-india-29373304

22 Shi Yinhong, “China’s Complicated Foreign Policy”, European Council on Foreign Relations, March 31, 2015, http://www.ecfr.eu/article/ commentary_chinas_complicated_foreign_policy311562

23 Naohiro Kitano and Yukinori Harada, “Estimating China’s Foreign Aid 2001 – 2013”, Comparative Study on Development Cooperation Strategies: Focusing on G20 Emerging Economies, No. 78 (2014), JICA Research Institute, Tokyo, p. 3; “China’s Second White Paper on Foreign Aid”, Issue Brief, United National Development Programme, South South Cooperation China, No. 5 (2014), August, http://www.cn.undp.org/content/dam/china/docs/Publications/UNDP-CH-ISSUE%20BRIEF.pdf

24 Ishaan Tharoor, “What China’s and Pakistan’s Special Friendship Means”, The Washington Post, April 21, 2015, http://www.washingtonpost.com/blogs/worldviews/wp/2015/04/21/what-china-and-pakistans-special-friendship-means/

25 Salman Masood and Declan Walsh, “Xi Jinping Plans to Fund Pakistan”, The New York Times, April 21, 2015, http://www.nytimes.com/2015/04/22/world/asia/xi-jinping-plans-to-fund-pakistan.html?_r=0

26 Saud Mehsud and Maria Golovnina, “From his Pakistan Hideout, Uighur Leader Vows Revenge on China”, March 14, 2014, Reuters, http://www.reuters.com/article/2014/03/14/us-pakistan-uighurs-idUSBREA2D0PF20140314

27 M Ilyas Khan, “China's Xi Jinping Agrees $46bn Superhighway to Pakistan”, BBC News, Asia, April 20, 2015, http://www.bbc.com/news/world-asia-32377088

28 “Security Fears for China-Pakistan Corridor as Xi Ends Visit”, Daily Mail, Mail Online, April 21, 2015, http://www.dailymail.co.uk/wires/afp/article-3048553/Security-fears-China-Pakistan-corridor-Xi-ends-visit.html

29 Baqir Sajjad Syed, “Special Force to Protect Corridor Projects”, Dawn, April 21, 2015, http://www.dawn.com/news/1177491/special-force-to-protect-corridor-projects

30 M Ilyas Khan, “China's Xi Jinping Agrees $46bn Superhighway to Pakistan”, op. cit.

31 Andrew Stevens, “Pakistan Lands $46 Billion Investment from China”, op. cit.

32 Graham T. Allison, “Obama and Xi Must Think Broadly to Avoid a Classic Trap”, New York Times, June 6, 2013, http://www.nytimes.com/2013/06/07/opinion/obama-and-xi-must-think-broadly-to-avoid-a-classic-trap.html?_r=0

33 François Godement, “Explaining China’s Foreign Policy Reset”, European Council on Foreign Relations, Asia Centre, China Analysis, April (2015), Special Issue, pp.2-3.

34 François Godement, “China’s Neighbourhood Policy”, European Council on Foreign Relations, Asia Centre, China Analysis, February (2014), http://www.ecfr.eu/page/-/China_Analysis_China_s_Neighbourhood_Policy_February2014.pdf

35 Shannon Tiezzi, “Why China Embraces Narendra Modi”, The Diplomat, May 29, 2014 http://thediplomat.com/2014/05/why-china-embraces-narendra-modi/

36 François Godement (2015), “Explaining China’s Foreign Policy Reset”, op. cit.

37 Salman Masood and Declan Walsh, “Xi Jinping Plans to Fund Pakistan”, op. cit.

38 Ishaan Tharoor, “What China’s and Pakistan’s Special Friendship Means”, op. cit.

39 Khaleeq Kiani (2015), “$28bn Accords for Fast-track Projects”, Dawn, April 21, http://www.dawn.com/news/1177233/28bn-accords-for-fast-track-projects

40 Ibid.

41 Ibid.

42 Ibid.

43 Ibid.

44 Ibid.

45 Chinese President Xi is Making a $46 Billion Move in Pakistan, Business Insider, April 20, 2015, http://www.pcgv.org/April%2020%202015.pdf

46 Minxin Pei, “Why China Keeps Throwing Trillions in Investments Down the Drain”, Fortune, December 1, 2014, http://fortune.com/2014/12/01/china-investment-losses-infrastructure/

47 Ibid.

48 Zhang Chun (2014), “Why doesn't Anyone like Chinese Companies Overseas?”, China Dialogue, September 12, https://www.chinadialogue.net/article/show/single/en/7299-Why-does-no-one-like-Chinese-companies-overseas-

49 Ibid.

50 Discussion with Research Fellows with Deputy Director General, Nagendra K Saxena, Indian Council of World Affairs, 28 April 2015.

51 Nicklas Norling, “The Emerging China-Afghanistan Relationship”, Central Asia-Caucasus Institute Analyst, May 14, 2008, http://www.cacianalyst.org/?q=node/4858/print

52 Charles Wallace, “China, Not U.S., Likely to Benefit from Afghanistan's Mineral Riches”, Daily Finance, June 14, 2010, http://www.dailyfinance.com/2010/06/14/china-us-afghanistan-mineral-mining

53 Jason Heeg, “Chinese Imperialism in 2013: Application of Unrestricted Warfare or the Legitimate Use of the Economic Instrument of National Power?”, The Foreign Military Studies Office (FMSO), (2014), Fort Leavenworth, United States, http://fmso.leavenworth.army.mil/Collaboration/Interagency/chinese-imperialism.pdf

54 Amir Mir, “China Seeks Military Bases in Pakistan”, South Asia Times, October 26, 2011 http://www.atimes.com/atimes/South_Asia/MJ26Df03.html

55 Monika Chansoria, “China Makes its Presence Felt in Pak Occupied Kashmir”, The Sunday Guardian, April 27, 2015, http://www.sunday-guardian.com/analysis/china-makes-its-presence-felt-in-pak-occupied-kashmir

56 “India should be Upfront in Voicing Opposition to China-Pakistan Economic Corridor”, Business Standard, April 21, 2015, http://www.business-standard.com/article/news-ians/india-should-be-upfront-in-voicing-opposition-to-china-pakistan-economic-corridor-115042100473_1.html

57 Brig. Vinod Anand, “China-Pakistan Economic Corridor: Prospects and Issues”, Vivekananda International Foundation, April 8, 2015, www.vifindia.org/print/2481

58 “China Protests at Modi's Visit to Disputed Arunachal Pradesh” (2015), Reuters, February 21, 2015, http://in.reuters.com/article/2015/02/21/china-india-territory-idINKBN0LO1LA20150221

59 Dipanjan Roy Chaudhury, “India Plans Cotton, Ancient Maritime Routes to Counter China's Ambitions”, Economic Times, April 17, 2015, http://articles.economictimes.indiatimes.com/2015-04-17/news/61253559_1_maritime-silk-road-indian-ocean-chinese-silk

60 “Why this Iran Port is Important”, The Economic Times, October 23, 2014 http://articles.economictimes.indiatimes.com/2014-10-23/news/55358943_1_gwadar-chabahar-port-chahbahar