Indian Council of World Affairs

Sapru House, New DelhiElections in Chile

Source: Google Maps

Billionaire former President (2010-2014) Sebastián Piñera’s victory in Chile’s presidential election run-off, on December 17, 2017, is seen as an expansion of the right in South American politics, following the rise of conservative politics in Argentina, Brazil, Paraguay and Peru. The 68-year old rightist defeated the center-left television journalist Mr. Alejandro Guillier by a securing 54.6 out of the 99 per cent votes that were counted. The run-off was a sequel to the first round of polling on November 19, 2017, in which Mr. Piñera of the Chile Vamos (Let’s Go, Chile) coalition got 36.64 per cent of the vote against his nearest rival Mr. Guillier’s 22.70 per cent. Although he was more than 10 per cent ahead of his opponent, Mr. Piñera was short of the 50 per cent required for an outright win required to avoid a run-off.i Mr. Piñera, would be taking office on March 11, 2018. Under Chile’s 1980 constitution, a president can serve only one non-consecutive term and, therefore, the incumbent President Michelle Bachelet could not contest.

Many Chileans in the electorate of 14.3 million did not participate in the election and the low turnout appears to be on account of political apathy. According to CEP polling data, 47 per cent of voters said that they have no interest in politics. In the first round, in spite of eight candidates from across the political spectrum, voting was just 46.7 per cent. Even in the run-off, only 44 per cent of the electorate voted. For the first time, 39,137 Chileans in 54 countries -- who together account for four per cent of Chile’s 18 million -- could vote, thanks to President Bachelet’s reform measure of 2014 which allows non-resident Chileans to vote in the presidential election.

Mr. Piñera’s election campaign was dominated by a number of key issues. The campaign focussed on reinvigorating the flagging economy, reforming the corporate tax code, improving pensions and eliminating unnecessary state spending programmes. He pledged to create thousands of new “quality” jobs and maintain free higher education for most students. To mollify the middle class, he has called for extra public spending of US$14 billion -- or 1.4 per cent of GDP per year -- over the next four years. This would be spent on pensions, health, infrastructure and education, including free nursery schools. Mr. Piñera said that half of this amount would come from higher growth and the balance from reduction of “ineffective” and “unnecessary” spending. The overall tax burden would be around 20 percent of GDP.

Mr. Guillier, a former news anchor, was the candidate of the Social Democrat Radical Party and the governing New Majority (Nueva Mayoría) coalition led by President Bachelet. During the campaign, he pledged to continue the reform agenda of the Bachelet administration. The major reform agenda was to increase spending on health, education and pensions; improve access to abortions; greater autonomy and authority for local government; wider recognition of indigenous rights; and, shoring up the welfare state.

Since Chile’s return to democracy in 1990, Mr. Piñera, a businessman whose fortune is estimated at US$1.2 billion, is the only center-right politician to have defeated the Coalition of Parties for Democracy (Concertación) (the Party for Democracy, the Socialist Party, the Christian Democratic Party and the Democratic Socialist Radical Party). Mr Pinera’s victory in the first round was considered a rebuke to President Bachelet and it also reflected the divisions among the left. The Christian Democratic Party (Partido Demócrata Cristiano) decided to split from President Bachelet’s New Majority coalition and, for the first time, field its own candidate. It was also because of diminished public support and dislocation within President Bachelet’s seven-party leftist coalition. Her popularity plummeted from 84 percent at the end of her first term in 2010 to 23 percent in 2017.ii President Bachelet’s administration has been plagued by corruption scandals and those involved include one of Chile’s largest financial groups, the Penta Group, and the rightist party, Independent Democratic Union (Unión Demócrata Independiente) (UDI).iii More importantly, one of the scandals involved President Bachelet’s son, Sebastián Dávalos. He was accused of using his political influence to arrange a US$10-million bank loan for his wife’s firm, Caval, which then used the funds to buy land in central Chile that was promptly resold for profit.iv The national banking regulator rejected the allegations against Mr. Dávalos, but Congress set up an investigative committee to look into the allegations.v In addition, Chile’s economy has slowed down considerably, along with the other economies of South America, due to a significant fall in commodity prices. Another factor in Mr. Piñera’s victory was the splitting of the Coalition of Parties for Democracy, after the center-left and centrist parties decided to go their own way.

Economic Problems and Changing Political Scenarios

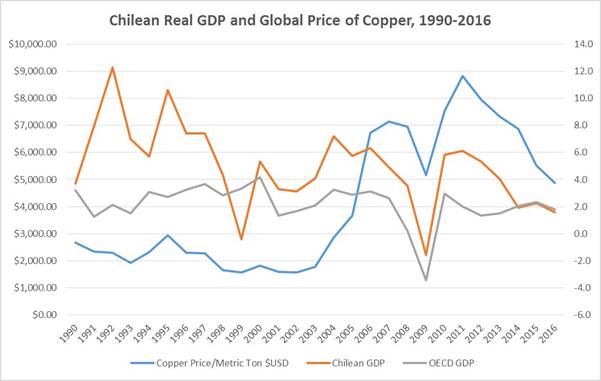

For nearly three decades, the Coalition of Parties for Democracy maintained a strong political and economic bloc after defeating General Augusto Pinochet’s military rule in a 1988 plebiscite. In that period after the dictatorship, the Coalition of Parties for Democracy focused on inclusive growth for improving the livelihood of Chileans. From 1990 to 2011, when global copper prices peaked, the economy grew at an average rate of 5.5 per cent per year. Poverty also declined significantly, from 68 percent in 1990 to 14.4 percent in 2013. However, while family incomes have risen and poverty has halved since 2006, Chile is the most unequal country in the OECD in terms of income, wealth and opportunity, and falls shy of OECD averages in most well-being indicators. According to World Bank figures, inequality in Chile has declined since 1990, but was higher than that of neighbours Peru and Argentina in 2013.

Since 2006, President Bachelet has been able to deliver on some of her reformist platform, including on issues of taxation, education, and campaign finance. But by August 2016, President Bachelet’s approval rating had dropped to just 19 per cent, according to an Adimark survey—the lowest rating of any president since Chile’s return to democracy.vi Her approval rating improved slightly, going up to 35 percent in August 2017, but that did not hold. According to a survey at the end of October 2017 by the Santiago-based think tank, Center for Public Studies (Centro de Estudios Públicos, CEP), 64 per cent of Chileans indicated that they do not trust the president and only 23 percent approved of the way she has led the government – which is in sharp contrast to the 84 per cent approval rate she enjoyed at the end of her first term in 2010.vii

Historically, Chile has been heavily dependent on copper exports, which account for approximately 20 per cent of the GDP and over half of all exports. Copper prices peaked in 2011, during the second year of the first Mr. Piñera administration; but by the beginning of President Bachelet’s second term, Chile initiated an open-market economy. However, from 2015-2016, global copper prices declined by 22 per cent and real GDP fell from 4 per cent in 2013 to 1.5 per cent in 2017. It coincided with President Bachelet’s increased social spending, which weakened investor confidence. In 2015, President Bachelet unsuccessfully attempted to rewrite the Pinochet-era constitution, promoting a fully democratic version with free education and tax reforms. These reforms were criticised by political forces on both sides.

Source: OECD and Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis

Challenges to Chile’s Next President

Mr. Piñera’s victory has raised hopes in the domestic market and among investors of more investor-friendly policies though he would be faced with a determined opposition in Congress. Mr. Piñera would also have to face the leftist coalition which has promised to fight his plans to reduce taxes and “refine” the progressive policies undertaken by President Bachelet. In this context, any initiative for reform may find it difficult to gain approval.

Economic challenges and the slowing down of the economy in recent years have resulted in growing disapproval of the current government. Poor growth rates and political rivalry have plagued Bachelet’s second stint as president. This led to diminished electoral support for the ‘New Majority’ ruling coalition while, at the same time, boosting support for Mr. Pinera. In President Bachelet’s initial two years, the economy grew at 1.5 per cent per year and economic growth is likely remain low. According to the IMF, Chile can only grow by 2.3 per cent annually over the next four years.viii

The underperformance of the Chilean economy would not draw investors and this would mean political friction besides creating a conflict of interest within the government. For example, in August 2017, the executive authority stopped the iron-ore project worth US$2.5 billion as a result of which Chile’s entire Economic Team resigned.ix Although President Bachelet has defended her decision on environmental grounds, it has led to serious divisions within the Bachelet Administration.

Although the victory of Mr. Pinera is likely to kindle the Chilean economy, the low social confidence in the country’s political system poses a threat to the long-term stability. In view of the sluggish economy, the newly-elected president has charted a route to overcome the hardship facing the country. Whether it would work remains to be seen.

****

* The Author, Research Fellow, ICWA, Indian Council of World Affairs, New Delhi.

Disclaimer: The views expressed are that of the Researcher and not of the Council.

Endnotes

i In Chile, a two-round system is used for presidential election. In order to win the election in the first round, the winning candidate’s party must receive more than 50 percent of the valid votes. Should there be more than two candidates in the presidential election, with none of them obtaining more than half of the votes validly cast; a new election shall be held. The second election (“balloting”) being held on the fourth Sunday after the first election has been routine in every election since 1990, and limited to the top two candidates when no candidate gains 50 percent of vote.

ii Daniela Mohor, “The Mixed Legacy of Michelle Bachelet,” November 16, 2017, https://www.usnews.com/news/best-countries/articles/2017-11-16/chiles-election-serves-as-a-referendum-on-michelle-bachelets-domestic-legacy, Accessed on November 27, 2017.

iii Pascale Bonnefoy, “Executives are Jailed in Chile Finance Scandal,” March 7, 2015, https://www.nytimes.com/2015/03/08/world/americas/executives-are-jailed-in-chile-finance-scandal.html, Accessed on November 27, 2017.

iv “Chilean President Asks Cabinet to Resign,” May 7, 2015, http://www.bbc.com/news/world-latin-america-32620121, Accessed on November 27, 2017.

v Pascale Bonnefoy, “President of Chile Removes Five From Cabinet in a Shake-Up,” May 11, 2015, https://www.nytimes.com/2015/05/12/world/americas/president-michelle-bachelet-chile-reshuffles-cabinet-ministers.html?_r=0, Accessed on November 27, 2017.

vi Karina martin, “Chile’s President Bachelet with 24% Approval Ratings after Forest Fires Crisis,” March 6, 2017, https://panampost.com/karina-martin/2017/03/06/chiles-president-bachelet-with-24-approval-ratings-after-forest-fires-crisis/, Accessed on November 28, 2017.

vii Daniela Mohor, “The Mixed Legacy of Michelle bachelet,” November 16, 2017, https://www.usnews.com/news/best-countries/articles/2017-11-16/chiles-election-serves-as-a-referendum-on-michelle-bachelets-domestic-legacy, Accessed on November 28, 2017.

viii World Economic Outlook, “Real GDP Growth,” http://www.imf.org/external/datamapper/NGDP_RPCH@ WEO/OEMDC/ADVEC/WEOWORLD/CHL, Accessed on January 1, 2018.

ix Javiera Quiroga, “Chile’s Entire Economic Team Resigns in Government Crisis,” August 31, 2017, https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2017-08-31/chile-s-finance-minister-valdes-resigns-in-government-crisis, Accessed on January 1, 2018.