Indian Council of World Affairs

Sapru House, New DelhiAustralia-Indonesia: Time to revisit relations

There have been several narratives which have outlined the distinct bilateral relationship between Australia and Indonesia. The relations based on historical connections and growing defence, security and strategic ties have been broad-based and constantly evolving. However, at the same time, it has also witnessed its own share of ups and downs but nevertheless it has been revived from time to time, with both sides indicating a desire to stabilise and develop the relationship.

As delineated in government documents, Australia has “a clear national interest in a prosperous, peaceful and secure South-East Asia in which countries cooperate to resolve common problems. It has long recognised the benefits of supporting regional processes for promoting peace and economic growth.”1 Indonesia’s strategic location in the Indo-Pacific Ocean covering the northern part of Australia through which more than 60 per cent of Australia’s exports pass, makes it one of the most important neighbours for Australia. Along with India, Australia argued for Indonesia’s independence from the Dutch rule. Indonesia’s central role in Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) as well as in Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation (APEC) and ASEAN Regional Forum (ARF), along with its significance as a trading and investment partner often puts spotlight into the oft-quoted comment that “Australia needs Indonesia more than Indonesia needs Australia”.

Fluctuating relations: A brief historical overview of the relations

Australia’s relations with Indonesia go back to the time when in 1945 Australian Prime Minister Ben Chifley advocated Indonesia’s independence struggle through the promotion of the policy of self-determination. He wanted nascent Indonesia to act as a barrier to the southward expansion of any Asian power potentially hostile to Australia. Problems started to emerge from the mid 1950s when President’s Sukarno’s support for the Partai Komunis Indonesia (PKI) aroused Australia’s suspicion. Sukarno needed protection from persecution by the Indonesian army whereas the PKI needed legal protection so as to establish a mass base of support. The erosion of democracy and the rise of the communist forces were not particularly liked by the Australian government. The conflicting policies over the West Irian issue (now Papua) and the Indonesian confrontation towards Malaysia were factors that further strained the relations between the two countries. The anti-communist New Order which emerged during Suharto’s tenure provided an opportunity to restore ties with Australia. Towards this end Paul Keating’s policy of engaging Southeast Asia and particularly Indonesia necessitated the need to dismiss the fear of Indonesia as an expansionist power. Emphasising on the growth of economy in Indonesia, Keating highlighted the new opportunities for cooperation which had originated because of progressive changes in the economy.2

The 1993 Strategic Review clearly indicated Australia’s strategic outlook towards Indonesia when it stated that “more than with any other regional nation, a sound strategic relationship with Indonesia does most for Australia’s security. We should seek new opportunities to deepen the relationship in areas that serve both countries’ interests.”3 In June 1994, Keating proposed formalizing defense ties between the two countries during his visit to Jakarta. On 18 December 1995, both the countries signed a watershed security treaty which came to be known as the Australia-Indonesia Agreement on Maintaining Security, the first security treaty signed between the two neighbours and the first ever signed by Indonesia with any other state. It provided de jure recognition of the extant de facto management system for the bilateral defense relationship. Trouble surged again in 1999 after Australia supplied a police contingent and troops for United Nations Mission for East Timor (UNAMET) and International Force for East Timor (INTERFET) respectively, which for Indonesia appeared violation of the treaty by Australia. After a review, in September 1999, Indonesia unilaterally took the decision to abrogate the Agreement.4 Since 1999, relations between Indonesia and Australia have remained strained. Throughout 2000, proposed visits to Australia by President Abdurrahman Wahid were postponed several times.

The East Asian Crisis of 1997 had a destabilizing effect on the rupiah and led to the decline in the demand for Australian products in the region.5 Indonesia which had recorded one of the fastest growth rates in the world between 1970 and 1996 (the economy grew by 7.2% per year, propelling an annual increase of 5.1% in per capita income) saw its financial weaknesses growing in number as exports growth slowed down and the banking system showed lack of supervisory and regulatory capacity.6 The bigger challenge was however perceived to be the sustenance of the economic recovery as Indonesia took control of the crisis with a combined average GDP growth of 4.6 per cent annually between 2000 and 2004.7

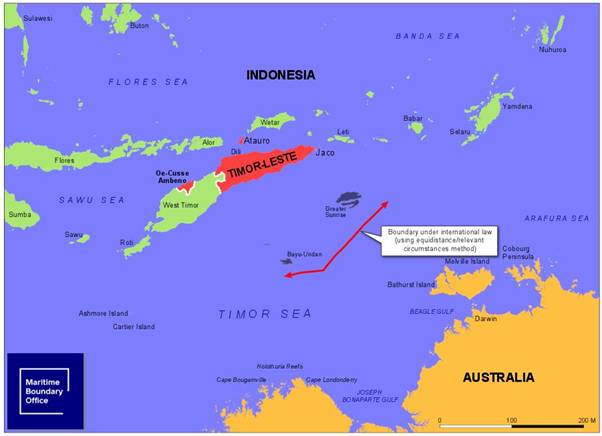

Maritime border disputes have been a characteristic feature of the relations during the later part of 1980s. After the Timor Gap Treaty was signed in 1989, Indonesia and Australia got to share resources in what was known as the Timor Gap. East Timor has long contended that the division of the border must be such that it places most of the Greater Sunrise oil and gas field in their territory. Though the Certain Maritime Arrangements in the Timor Sea (CMATS) was signed in 2006, yet no permanent border was set, and instead it ruled that revenue from the Greater Sunrise oil and gas field would be split evenly between the two countries. The ongoing dispute has now been referred to the Permanent Court of Arbitration in The Hague. It goes to say without doubt that the decision made in the Permanent Court of Arbitration over maritime boundaries would have far-flung repercussions on the otherwise lopsided history of bilateral relations.

Map 1: Map showing East Timor (Timor-Leste)

Source: Maritime Boundary Office, http://www.gfm.tl/learn/maps/ accessed February 7, 2017.

Australia and Indonesia: Unpredictable pattern of relationship

The post 9/11 period offered several opportunities for closer engagement between Australia and Indonesia. The assistance received in the form of 50 Australian Security Intelligence Organization and Federal police officers to Bali to assist Indonesian authorities with their investigation in the Bali bombings in 2002, where majority of Australians were killed, was welcomed by Indonesia. However, the Australian PM’s remarks that Australia reserved the right to take pre-emptive action to counter terrorist threats once again stirred apprehensions that Australia was seeking to conduct pre-emptive strikes in the region. Nonetheless, one of the most remarkable outcomes of the Bali bombings was the highly successful operational successes achieved between the AFP (Australian Federal Police) and POLRI (Indonesian police) in the forensic investigations. The camaraderie which developed between AFP Commissioner Mick Keelty and his POLRI counterpart Da’i Bachtiar formed the basis for some of the most effective institutional bridge building achieved between the two countries in over half a century.8

The Tsunami of December 2004 and Australia’s generous response to it in the form of commitment of 34.4 million dollars as humanitarian assistance to Indonesia, followed soon by the visit of Sushilo Bambang Yudhoyono to Australia further helped to cement the ties between the two countries. Australia also acknowledged Indonesia’s help in facilitating their entry to the East Asian Summit.

The relations between the neighbours reached a low point when a diplomatic row broke out between them in the wake of John Howard government’s decision taken in March 23, 2006 to grant temporary protection visas to 42 asylum seekers and their families from Indonesian Papua. Indonesia’s angry reaction included withdrawing its Ambassador from Canberra. After a brief freeze, official relations improved with the signing of the Treaty of Lombok in 2006 which required the two countries to support each other’s unity and territorial integrity and to refrain from the threat or use of force. The hardliner stance adopted by Prime Minister Tony Abbott in 2013 regarding resettlement of refugees from Southeast Asia in Australia emerged as a cause of concern for Indonesia as those refugees were turned back to Indonesian waters. Indonesia and Malaysia both agreed to provide humanitarian assistance to the 7000 Bangladeshi migrants and Rohingya refugees stranded at sea and provide temporary shelter for up to a year, while Australia clearly stated that it would not resettle them in Australian territories. A bilateral relationship already under pressure was further strained by the revelation which indicated that Australia had tried to monitor the mobile calls of Yudhoyono, his wife, senior ministers and confidants. In the same year, the execution of two Australian drug convicts created rifts among the countries after which both Australia and Indonesia recalled their respective ambassadors.

The issue of refugees still continue to pose as a deterrent for the smooth conduct of relations between the two countries. In 2015, tensions arose between the two parties after people smugglers told Indonesian police that Australian officials had paid hefty amounts of money to them in return for turning around a boat carrying 65 asylum seekers. The lack of answers from the Australian government regarding the allegations cast a shadow on Australia’s relationship with Indonesia.

Amidst all the strains and stresses in the relationship between Australia and Indonesia was the common goodwill prevalent among the two countries to counter the issue of Illegal, Unreported and Unregulated fishing (IUU) which was a source of diplomatic strain and environmental concern. A Joint Operation by the Australian Border Force (ABF), the Australian Fisheries Management Authority (AFMA) and the Indonesian Ministry of Marine Affairs and Fisheries was held in 2016 to check exploitation of natural resources in areas of mutual interest.

The above account of bilateral relations between Australia and Indonesia is indicative of the fact that relations over the years have been asymmetrical and bumpy. The presence of several areas of contestation has necessitated the building up of a common space where the two countries can amicably settle the disputes and come to mutually acceptable solutions. A precondition for this to happen, however would be to create an atmosphere of trust and the presence of the factor of political goodwill. The strategic significance of the Indo-Pacific region as an area of geopolitical importance in the 21st century also entails cooperation on sub-strategic maritime issues which is imperative for the establishment of regional stability and security. Australia and Indonesia can come together to enhance cooperation on several areas which can not only help to dissipate suspicion and build trust but also help to construct complementarities for achieving positive results.

Potential areas of cooperation:

- For Australia, there is considerable opportunity in Indonesia to expand their trade, investment and economic cooperation. Being the largest economy in Southeast Asia and the 16th largest economy in the world, Indonesia can offer to assist in broadening the base of merchandise trade. Australia can find investment opportunities in infrastructure and cattle breeding. It can invest in Indonesia’s digital economy, which has a potential to grow to 130 billion dollars in 2020. Australia was ranked as the 11th investment partner of Indonesia in 2015 which shows that the investment climate needs to be improved and more opportunities explored in order for the investment partnership to be enhanced. Table 1 presents Australian investment in Indonesia over a period of six years (2010-2015) which reveals that the investment has only been fluctuating sharply over the years. Indonesian investment in Australia is very meagre considering that based on capital expenditure, the investment realization in Australia was only 30 million USD.9 A dynamic trading partnership can be realised if both the countries can engage in commerce and cooperation in telecommunications, engineering, environmental technology, consumer goods and services, food processing, chemicals and pharmaceuticals. Table 2 depicts Australia’s trade in goods and services with Indonesia and as evident, the figures show a tardy growth. There is considerable opportunity to work on complementarities and take the economic partnership to a qualitatively new level. The successful conclusion of the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP) would also mean the way towards a comprehensive, high quality and mutually beneficial economic partnership that will cover trade in goods, services, investment, economic and technical cooperation.

Table 1: Australian FDI in Indonesia from 2010 to 2015 (in USD million)

|

2010 |

2011 |

2012 |

2013 |

2014 |

2015 |

Total |

|

214 |

90 |

744 |

226 |

647 |

105 |

2026 |

Source: Hariyoga, Himawan (Deputy Chairman of Investment Promotion), “Invest in Indonesia”, Investment and Business Establishment in Indonesia, November 19, 2015, file:///C:/Users/Lenovo/Downloads/IABW_BKPM_Kepala.pdf accessed February 9, 2017.

Table 2: Australia’s trade in goods and services with Indonesia (A $ million)

|

2013-2014 |

2014-2015 |

2015-2016 |

% share of total |

% growth 2014-2015 to 2015-2016 |

5 year trend |

|

15,993 |

14,879 |

15,314 |

2.3 |

2.9 |

1.8 |

Source: “Australia’s trade in goods and services”, Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade, Australian Government, December 8, 2016 http://dfat.gov.au/about-us/publications/trade-investment/australias-trade-in-goods-and-services/Pages/australias-trade-in-goods-and-services-2015-16.aspx accessed February 9, 2017.

- A common challenge which both the nations face is that of terrorism. Close coordination of neighbours by sharing intelligence and analysis can help to thwart off terror attacks. Exchange of technology and best practices can improve responses of governments. Even though there has been substantial cooperation happening but with the emergence of new ISIS affiliates, there is need for better coordination.

- Non-traditional threats like global warming, protecting the global commons, countering cyber threats and ensuring energy security have become causes of concern for nations and entities at large. Both Australia and Indonesia lie in a sensitive geo-political sphere and rapid degradation of the environment could lead to serious complications. Conflicts could escalate, given the fact that the two countries have not had a smooth bilateral relationship. Climate change can also reverse agricultural export and import trends. It is hence necessary to elevate the partnership to make it truly broad-based and futuristic.

- In recent times the threat of cyber attack has been recognised as a serious problem by the Australian government. The 2015 cyber attack on the Bureau of Meteorology (BoM), which owns one of Australia’s largest super computers, showed how sensitive systems across the Federal Government were targeted. In view of the gravity of the challenge, which has now persisted over for some time, Australia’s six intelligence agencies have been under a review so as to ensure appropriate responses to security threats.10 A lack of cyber security has also landed Indonesia in a ‘cyberattack emergency’ which necessitated the need for a coordinated cyber defense policy.11 The bigger problem is however the recognisance of the fact that cyber threats do not respect boundaries and often have critical infrastructures as their targets. Australia and Indonesia have both identified that cyber threats are an emerging security issue. It was in this recognition of the magnitude of the problem that during the recent 2+2 Dialogue in Bali in October 2016, both countries agreed to forge cooperation on capacity building within the framework of security and cyber crime. Such a cooperation could be expanded to form joint and rapid action forces which can deal promptly with cyber attacks for damage control and retrieval of crucial data. A welcoming development has been the focus placed on strengthening cyber security in the recently concluded third ministerial council meeting on February 2, 2017 on Law and Security, despite the ongoing military suspension between the countries.

- Integrating energy needs and ensuring commitment towards the goals and commitments of climate change has been undertaken by the Australian government of late to ensure harmonisation of requirements and responsibilities. On the other hand, Indonesia has been dependent on imports to meet its growing energy needs, though it has coal reserves, which however could exhaust by 2033, a study by PwC pointed out in 2016.12 Keeping in mind environmental concerns and pressure to reduce carbon dioxide emissions, both countries can implement measures for a transition to a low carbon economy by the development and deployment of cost-effective low carbon technologies. It is within Australia’s interests as well to safeguard their commitment of reducing carbon emissions and supporting policies that keep investments away from fossil fuels. This would require, inter alia, strengthening of institutional mechanisms, coordinated systems of energy management and exchange of policy experience and best practices. Both countries can further cooperate on mutually beneficial shared projects and seek cooperation on new innovation techniques to address the demand for energy supply.

- In President Joko Widodo’s dynamic maritime doctrine, the sea has an increasingly important role in determining Indonesia’s future. For rebuilding its maritime culture, development of maritime infrastructure and connectivity within and beyond and maintaining the safety of shipping and maritime security, one of the essential conditions is to build peaceful partnerships with neighbours. Australia being its closest, has considerable stakes in ensuring the safety and security of the Pacific and Indian Ocean region (PACINDO) and for preventing the source of conflicts at sea such as illegal fishing, violations of sovereignty, territorial disputes, piracy and marine pollution.

- There is a need to upgrade the defence industry and military modernization cooperation between Australia and Indonesia as maintaining peace and security constitutes a common goal for regional peace and stability. By conducting joint military exercises, promoting intelligence sharing to counter common threats and exchanging technology and customizing it to suit operational capabilities, the two countries can enhance defense cooperation. In view of evolving threats, there is a need to expand strategic dialogues to discuss piracy, securing maritime routes, strengthening oil exploration programmes, counter-terrorism and trans-national crimes. While Indonesia isn’t a member of the Regional Cooperation Agreement on Combating Piracy and Armed Robbery against Ships in Asia (ReCAAP), both countries participate in the Information Fusion Centre in Singapore, which deals with maritime security threats and incidents and have posted naval liaison officers there. The resolution of maritime dispute over sharing of resources of Timor Sea would be favourable for both countries for the purpose of exploring joint oil exploration programmes. Meanwhile, continued cooperation between Australian Federal Police and Indonesian National Police, as per agreement of 2015, to jointly prevent and combat transnational crimes is important for identifying and taking action on crimes that affect both the countries.

- Tourism and education sectors have exhibited considerable and profitable opportunities for expanding bilateral relations. In 2016, 95 per cent of visa applications from Indonesian students were reportedly approved and issued by the Australian embassy.13 Scholarship programmes and workshops and conferences aiming to build greater interaction among peoples of the region, attractive packages to cover living costs of Indonesian students studying in Australia and provision of English language training can attract more students who want to pursue higher education in Australia. Tourism is also a thriving sector which can be a cornerstone towards strengthening the relationship between the two countries. A record number of Indonesians travelled to Australia in June 2016, which was up by more than 43 per cent over the same month in 2015.14 On the other hand, as per 2016 data, more than 1 million Australians already visit Indonesia every year, contributing 8 trillion rupiah (1.8 billion dollars) to the local economy.15 The visa-free policy of the Indonesian government announced in 2016 has been introduced as a part of a plan to lure more visitors to Indonesia, as the government aims to attract at least 20 million foreign tourists to the country over the next five years. Tourism development between the two countries can lead to creation of favourable conditions for effective cooperation in other sectors as well.

- Indonesia is a growing power not only in Southeast Asia but also in ASEAN. Australia’s relations with Indonesia can be considered a determining factor to assess the nature of its relationship with ASEAN. For Australia, engaging with ASEAN is vital to secure regional stability. Opportunities for economic partnerships and fighting common challenges reflect the need for strengthening ties with ASEAN for guaranteeing Australia’s domestic security as well. The First ASEAN-Australia Biennial Summit held on September 7, 2016 highlighted the importance of this strategic partnership. It is hence significant for Australia to maintain cordial and effective relations with Indonesia and develop a shared vision of regionalism with ASEAN to shape the evolving political, strategic and economic architecture of the region.

Conclusion:

While the effectiveness of sectoral cooperation between Australia and Indonesia is difficult to pronounce correctly as it is still evolving, yet it must be noted that a blueprint based on mutual concerns and understanding would help in greater regional integration. Undoubtedly, the region where Australia and Indonesia enjoy geographical proximity is a neighbourhood which is also crucial for the stability of the greater Indo-Pacific region in which emerging players like India and Vietnam also have larger and long term interests. The changing regional geopolitics and geo-economics require that the two countries develop close partnerships. Australia also has considerable stakes in implementing and developing Widodo’s strategic outlook of a Global Maritime Fulcrum for Indonesia. In the dynamics of substantial transformation of maritime dialectics and Indonesia’s shift in its maritime outlook, Australia and other neighbouring nations have a considerable scope in the realm which seeks to throw emphasis on building bilateral and multilateral engagements related to the maritime sector. Settlement of maritime disputes with Australia in this connection could enable better maritime diplomacy and ensure smooth conduct of Indonesia’s ‘outward looking’ policy to reach out to potential partners. Indonesia-Australia partnership is also vital to secure the promotion of the sustained growth and balanced development of the Indian Ocean Rim Association (IORA) region and to create common ground for regional economic cooperation.

***

* The Author is a Research Fellow with the Indian Council of World Affairs, New Delhi.

Disclaimer: Views expressed are of authors and do not reflect the views of the Council.

ENDNOTES

1 “Development assistance: ASEAN and East Asia Regional”, Australian Government, Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade, n.d., http://dfat.gov.au/geo/east-asia/development-assistance/Pages/development-assistance-in-east-asia.aspx accessed January 24, 2017.

2 Indonesia’s economy grew five and a half times since 1966. The percentage of people living below the poverty line fell from 40 per cent in 1976 to around 17 per cent in 1987. An economy which was heavily dependent on commodities was transformed, reformed and deregulated. (Ryan, Mark (ed.), “Advancing Australia: The Speeches of Paul Keating, Prime Minister,” (Sydney: Big Picture Publications, 1995).

3 Gordon, Michael, “A true believer: Paul Keating” (Brisbane: University of Queensland Press, 1993), p.139 in Singh, Bilveer, “Defense Relations between Australia and Indonesia in the Post Cold War Era”, (London: Greenwood Press, 2002).

4 Weatherbee, Donald E. (ed.), “International Relations in Southeast Asia: The Struggle for Autonomy”, USA: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, 2005, p. 47.

5 The external value of the Indonesian currency depreciated by over 80 per cent since July 1997.

6 Radelet, Steven, “Indonesia: Long Road to Recovery”, Harvard Institute of International Development, March 1999, http://www.cid.harvard.edu/archive/hiid/papers/indonesia.pdf accessed January 27, 2017.

7 “Indonesia – Investments”, December 26, 2016 http://www.indonesia-investments.com/finance/macroeconomic-indicators/gross-domestic-product-of-indonesia/item253? accessed January 27, 2017.

8 Mackie, Jamie, “Australia and Indonesia: Current Problems and Future Prospects”, Lowy Institute Paper 19, 2007, https://www.lowyinstitute.org/sites/default/files/pubfiles/Mackie,_Australia_and_Indonesia_1.pdf accessed January 27, 2016.

Within hours of the blasts, POLRI and AFP discussed ways to provide assistance to each other in investigation procedures. Arrangements for Australian-Indonesian police cooperation were formalised through a joint operation agreement on 18 October 2002. The operational successes and considerable level of interoperability in a number of areas achieved in this operation ensured cooperation between POLRI and AFP towards major counter terrorism operation in the next few years, including the 2003 Marriott Hotel bombing, the 2004 Australian embassy bombing and the 2005 Bali bombings.

9 Hariyoga, Himawan (Deputy Chairman of Investment Promotion), “Invest in Indonesia”, Investment and Business Establishment in Indonesia, November 19, 2015, file:///C:/Users/Lenovo/Downloads/IABW_BKPM_Kepala.pdf accessed February 9, 2017.

10 Wore, David, “Intelligence agencies face major review in new security era”, The Sydney Morning Herald, September 18, 2016, http://www.smh.com.au/federal-politics/political-news/intelligence-agencies-face-major-review-in-new-security-era-20160918-griyue.html accessed January 29, 2017.

11 “Cyberattacks in Indonesia rising at an alarming rate”, The Jakarta Post, June 3, 2016, http://www.thejakartapost.com/news/2016/06/03/cyberattacks-in-indonesia-rising-at-alarming-rate-officials.html accessed January 29, 2017.

12 “Indonesia could deplete coal reserves by 2033”, Reuters, March 7, 2016, http://www.reuters.com/article/indonesia-coal-idUSL4N16F4C4 accessed February 6, 2017.

Indonesia has signed contracts with the US that will ensure supply of natural gas from the US to Indonesia in 2018. Currently, Indonesian imports are led by refined petroleum, followed by crude petroleum. The top import origins of Indonesia are China, Singapore, Japan, South Korea and Malaysia.

13 “Commonwealth Bank eyes Indonesian students in Australia”, The Jakarta Post, January 16, 2017, http://www.thejakartapost.com/life/2017/01/16/commonwealth-bank-eyes-indonesian-students-in-australia.html accessed February 7, 2017.

14 “Australian and Indonesian tourists make history”, Australian Embassy, Indonesia, August 5, 2016, http://indonesia.embassy.gov.au/jakt/MR16_042.html accessed February 7, 2017.

15 Topsfield, Jewel, “Australian tourists finally granted free entry to Indonesia”, The Sydney Morning Herald, March 23, 2016, http://www.smh.com.au/world/australian-tourists-finally-granted-free-entry-to-indonesia-20160322-gnovx3.html accessed February 7, 2017.