Indian Council of World Affairs

Sapru House, New DelhiFormalising Skills, Encouraging Mobility: A Case Study of Sri Lanka’s Skills Passport and Bahrain’s New Work Permit

1. Introduction

The Skills Passport is an important tool that gives the prospective employee proof of qualification and skill sets when applying for jobs. It is a document or a tool that helps the workforce in the informal economy earn a living through their skills. A documented proof allows them to showcase their skills, qualifications and work experiences to prospective employers and works as a great portability tool.[i] For migrant workers, who come from different villages, towns and cities without documented proof of their skills, the Skills Passport becomes a systematic way of formally acknowledging their competencies.

India’s neighbouring country, Sri Lanka, also a Colombo Process Member State, has devised the National Skills Passport initiative for its returnee migrant workers, during the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020, to re-employ them in the economy with recognised skill sets and experience. The main objective of this initiative is to facilitate upward mobility in employment and entrepreneurial opportunities for returnee migrant workers in Sri Lanka and beyond.[ii] This paper will look at the National Skills Passport initiative by the Government of Sri Lanka and the overall structure, the benefits of the initiative and the process of implementation of the National Skills Passport in the context of Sri Lanka. The paper will also touch upon Bahrain’s New Work Permit introduced in October 2022.

2. National Skills Passport in Sri Lanka - Paving the Way

The National Skills Passport in Sri Lanka, launched on World Youth Skills Day in 2020, was developed by the Tertiary and Vocational Education Commission (TVEC), the apex body of Technical and Vocational Education and Training (TVET). It is a smart card that digitally stores the cardholder’s National Vocational Qualification (NVQ) and contains one year of documented work experience of the cardholder. It has been introduced by the TVEC of the Ministry of Skills Development, Employment and Labour Relations, along with the Employers' Federation of Ceylon (EFC) and the International Labour Organization (ILO). The Skills Passport is a unique and comprehensive informal portfolio of skills and qualifications of a worker that enables both employers and workers of Sri Lanka to compare the skills with various skills assessment frameworks. It is majorly recognised as the pathway to finding a job and accessing further training for reskilling and upskilling.[iii]

The rationale behind introducing the National Skills Passport in Sri Lanka is based on the need to recognise skills obtained, especially through informal experience, which is generally not considered. It aims to assess and certify skills and experience obtained through overseas employment, helping the repatriates of Sri Lanka gain employment opportunities in their country of origin. Moreover, the Skills Passport focuses on promoting entrepreneurship and a higher learning curve. This propels upward mobility in employment, leading to better wages and working conditions. Lastly, it opens up better career development avenues for migrant workers.[iv]

The Skills Passport, in essence, covers information on a worker's skills, expertise and experience and is also linked with a Recognition of Prior Learning (RPL) platform. This further fosters recognising informally acquired knowledge, skills and competencies through formal assessments and certifications.

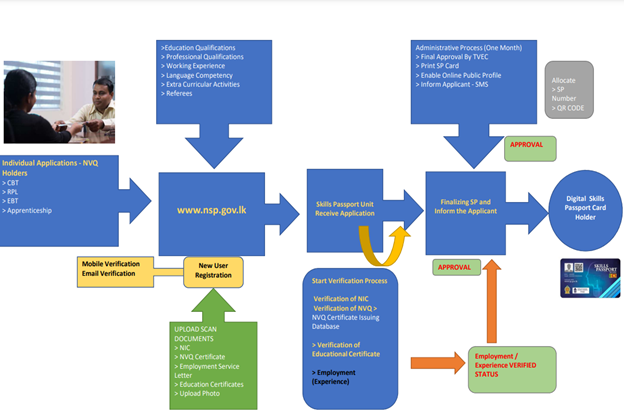

2.1 Implementation of the National Skill Passports

The Government of Sri Lanka has recognized two groups of returnee migrant workers as the major stakeholders that need attention in the implementation of the Skills Passport initiative. The first group includes the highly skilled returnee migrants, who are already skilled through the National Competency Standard (NCS), Recognition of Prior Learning (RPL) and National Vocational Qualification (NVQ). These applicants, based on their documented qualifications, are given additional skills training after which the Skills Passport application begins and their applications are forwarded to the Skills Passport Secretariat for approval. In the second group, the target stakeholders are the semi-skilled returnee migrants who undergo complete reskilling and upskilling through NVQ. This step becomes necessary as this target group lacks proper documentation of their skill set. The training period encourages them to recognise their potential in the workforce. They receive their NVQ certification thereafter. The rest of the application process remains the same for both categories of the returnee migrant workforce. Once they receive the Skills Passport, the process of reintegration into the workforce or self-employment begins.

The Skills Passport comes in the format of a chip-based card that contains all the details of the holder. It mentions the Name and Skills Passport ID of the holder along with a QR code. The QR code can be scanned to procure the details of the skills and prior experience of the worker, which is also linked with the National Skills Passport website.

Source: Sri Lanka’s National Skills Passport website

Presently, Sri Lanka’s National Skills Passport is only available for the returnee migrants of the country with the scope of employability within Sri Lanka. Efforts are underway to expand the Skills Passport to first-time migrant workers who are going to embark on their journey of employment. The Government of Sri Lanka is also working towards recognition of the National Skills Passport in its major countries of destination for smoother portability of skills and qualifications.

2.2 Benefits

The Government of Sri Lanka has outlined three-tier benefits of the Skills Passport, which are highlighted below.[v]

2.2.1 Workers’ Level: It helps in assessing the skills and experience of the workers and creates opportunities for higher learning and entrepreneurship. It also recognises and qualifies the skills obtained through informal experience, along with assessing and certifying skills and experiences obtained through local and overseas employment. It promotes upward mobility in employment, further leading to better wages and working conditions as well as providing opportunities for better career development and promoting entrepreneurship and higher learning skills.[vi]

2.2.2 Employers’ Level: It helps them identify the applicable workers with a specific skill set for various employment opportunities. It helps them employ the right persons for the job with specified skills, qualifications and experiences. The Skills Passport also reduces the costs and time needed for searching for qualified workers and shortens the recruitment process. Further, through appraisal, employees can be engaged in upskilling that will support their career development, pushing them to be more motivated and efficient.[vii]

2.2.3 Government’ Level: It helps the government to keep track of the employment sectors along with their skill type and utilize them to bridge the gaps in the labour market at both local and international levels. It also facilitates the government to match skills to opportunities directly for employment, further helping to streamline the migrant and returnee workers by skill type. It promotes long-term skills planning for economic development as well as attracts migrant returnee workers to industries such as construction, which are currently facing a surfeit of demand, with no local workers to bridge the gap.[viii]

Source: The Government of Sri Lanka’s presentation on Skills Passport at the seventh Thematic Area Working Group (TAWG) meeting on Skills and Qualifications Recognition Processes of the Colombo Process (CP) that took place in a hybrid modality in Bangkok on 21 June 2022.

2.3 Challenges

Although the Skills Passport is a useful tool in the recognition of skills in various labour mobility corridors within a country and between countries, it may face legal challenges and/or hurdles to its implementation in terms of variance in recognition accorded to skill sets in different countries and work environments.

Moreover, a long and tedious procedure of procurement of the Skills Passport will, tend to discourage prospective Skills Passport holders from procuring their cards. Instead, the entire process could be simplified, which allows the maximum number of returnee migrant workers to avail the opportunity for their career growth.

3. Bahrain’s New Work Permit: Another Initiative of a Migrant Dependent Nation

The Labour Market Regulatory Authority (LMRA) in Bahrain has launched the New Work Permit, bringing an end to the Flexi Permits in October 2022. Through this new permit, the Kingdom of Bahrain will link work permits issued to foreign immigrants to vocational and occupational credentials to increase safety and protection in workplaces.[ix] The registration process is online and will be facilitated through the LMRA website. The accredited centres will register and undertake the process of updating the data of workers in the Authority’s system.

Similar to the Skills Passport, Bahrain will be issuing a work permit card with a QR Code that will contain the prospective foreign worker’s updated data, including the type of permit, the occupation the worker is authorised to practice, the validity of the permit, health insurance details, and the name of the registration centres.[x]

4. Utility of the Skills Passport in India’s Context

In India, it is observed that every year, the number of migrant workers moving overseas has been steadily increasing as per available statistics.[xi] According to the eMigrate portal, a total of 4,16,024 Emigration Clearances were issued for ECR (Emigration Check Required) passports alone from 1 January 2020 to 30 June 2022.[xii] Also, in terms of remittances, growth is visible wherein India received a total of USD 87 billion in remittances in 2021[xiii] despite the impact of COVID-19 on the economy. However, a large number of the same Indian workers lack proper documentation when it comes to the recognition of their skills. As a result, in most cases, the workers neither get employed for the right job profile nor receive adequate monetary compensation for the skillset they possess. Considering that a skilled workforce is the future of employment, it will be beneficial for India to use this talent pool to the best of its ability to recognise the skill sets of prospective migrant workers. Here, it will be interesting to see how the Skills Passport can be applicable to the Indian context. The Skills Passport, if introduced in India, has the potential to become an influential instrument of immense relevance, especially to migrant workers moving overseas for employment opportunities. Further, the online system of the Skills Passport will simplify the task of matching opportunities for future employment easier. It has the potential to digitally transform the entire process of acquiring employment for Indian skilled workers not only within India but also overseas. This will further strengthen India’s digital inclusion and transformation model outlined by the Prime Minister, Narendra Modi, at the recently held G20 summit in Bali, Indonesia.[xiv]

5. Conclusion

Skilling is slowly becoming the future of employment across the world. Regularly updating one’s skill set is crucial for personal growth that trickles down to all sectors of the economy. In many instances, one may be skilled but still, be unemployed. In that scenario, the concept of a Skills Passport becomes a useful tool for economies that employ a large number of migrant workers in informal sectors. It provides adequate recognition of skills and certification to migrant workers who are often unable to show proof of their acquired skills as well as provides employers with the opportunity to engage with a skilled workforce. The National Skills Passport of Sri Lanka is an example that has shown potential for growth and inclusion of the returnee migrant workers in Sri Lanka’s economy. It also pushes returnee migrant workers towards an entrepreneurial mindset to make them self-sufficient. A similar model may also be adopted by India to recognise the skills of India’s migrant workers in the informal economy. As India is among one of the highest labour-sending countries in Asia, the Skills Passport can prove to be an important mechanism to officially provide skills certification for employment and re-employment purposes, both within India and overseas. In the overseas market, the Skills Passport can be a tool that benefits Indian workers and can enhance India’s stature as a provider of skilled migrant workers, as well as a Skilled Nation.

*****

*Oonmona Das, Research Intern, Indian Council of World Affairs, Sapru House, New Delhi.

Disclaimer: The views are of the author.

Endnotes

[i] Author, G. (2019, January 4). Skills passport – a doorway to informal workforce's upward mobility. National Skills Network. Retrieved November 11, 2022, from https://www.nationalskillsnetwork.in/skills-passport/#:~:text=A%20Skills%20Passport%20is%20a,their%20knowledge%2C%20skills%20and%20competencies.

[ii] Tertiary and Vocational Education Commission, Sri Lanka. (2020). Sri Lanka National Skills Passport Project: Innovation and Learning Practice, Bridging Innovation and Learning in TVET (BILT) Project. UNESCO. https://unevoc.unesco.org/pub/migration-tvec-skills-passport.pdf

[iii] Ibid.

[iv] The rationale behind the Skills Passport initiative in Sri Lanka was presented as part of the seventh Thematic Area Working Group (TAWG) meeting on Skills and Qualifications Recognition Processes of the Colombo Process (CP) that took place in a hybrid modality in Bangkok on 21st June 2022, Chaired by the Government of Sri Lanka.

[v] SKILLS PASSPORT, SRI LANKA. (n.d.). http://www.nsp.gov.lk/

[vi] Ibid.

[vii] Ibid.

[viii] Ibid.

[ix] New labour registration programme begins today in Bahrain. (2022, December 4). DT News. https://www.newsofbahrain.com/bahrain/86267.html

[x] Ibid.

[xi] Sharma, Y. S. (2022, September 1). Employment rate among Indian youth dips in FY22. The Economic Times. https://economictimes.indiatimes.com/news/economy/indicators/employment-rate-among-indian-youth-dips-in-fy22/articleshow/93926631.cms

[xii] PTI. (2022b, July 21). 4,23,559 Indian migrant workers returned from ECR countries from June 2020-December 2021. The Economic Times. https://economictimes.indiatimes.com/nri/work/423559-indian-migrant-workers-returned-from-ecr-countries-from-june-2020-december-2021/articleshow/93030585.cms

[xiii] PTI. (2022, July 20). With $87 billion, India top remittance recipient in 2021: UN report. The Economic Times. https://economictimes.indiatimes.com/nri/invest/with-87-billion-india-top-remittance-recipient-in-2021-un-report/articleshow/93012012.cms

[xiv] (n.d.). PM Modi Pushes for “Truly Inclusive” Digital Access in Speech as India Handed G-20 Presidency. The Wire. https://thewire.in/government/modi-g-20-speech-digital-transformation