Indian Council of World Affairs

Sapru House, New DelhiUnderstanding the Venezuelan Crisis and Analyzing its Impact on India

Introduction

Venezuela, the nation with the world’s largest crude oil reserves[i], until a few years ago enjoyed political stability and healthy economic growth. The wealth generated from the export of its energy resources was channeled by the then government of President Hugo Chavez into various welfare schemes that allowed several Venezuelans to improve their standard of living. However, falling oil prices, global economic slowdown and the sanctions placed by the members of the Organization of the Americas against the Maduro government has led to hyper-inflation and a slump in the Venezuelan economy. Corruption and lack of supply of essential commodities has further aggravated the situation[ii].

This paper seeks to analyse the prevailing situation in Venezuela and the humanitarian crisis that has ensued. It also aims to investigate the effects of the current political turmoil in Venezuela on the India-Venezuela relationship.

Venezuela under President Nicolas Maduro

On 5 March 2013 President Chavez died of cancer and his successor, the then foreign minister Nicolas Maduro assumed his position temporarily. In the ensuing presidential elections, Maduro edged out his opponent Henrique Capriles by the narrowest of margins (1.6% points)- an election the opposition claimed was rigged[iii]. However, as President Maduro was promoted by former President Chavez as his successor, he could overcome the protests and assume power. The election coincided with the fall in oil prices which caused the South American nation to suffer an economic collapse.

Source: Real GDP Growth, International Monetary Fund (2019)

Figure 1 (Real GDP Growth[iv])

The above figure shows the worsening condition of the Venezuelan economy, which according to Jo-Marie Burt, an associate professor of political science and Latin American Studies at the Schar School of Policy and Government at George Mason University, happened because “Venezuela has long been dependent on oil revenues, and the Bolivarian revolution of Hugo Chavez did not fundamentally alter that situation. The decline of oil prices, the massive social spending of the Chavez and Maduro governments, US sanctions, and a combination of economic mismanagement and corruption at the top have contributed to the economic collapse.”[v]

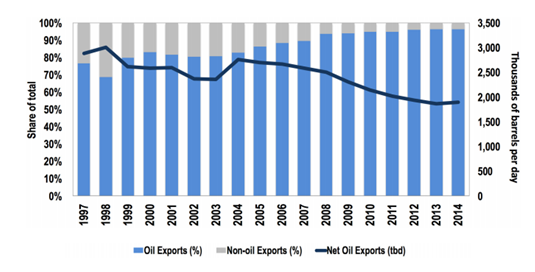

The heavily oil-dependent Venezuelan economy focused on exporting oil (Figure 2) and importing basic necessities like pharmaceuticals, cereals, dairy produce and electrical machinery[vi], instead of developing other natural resources and infrastructure, and consequently buckled when oil prices dropped. As a result, foreign demand for the bolívar decreased and foreign investors started looking elsewhere, which devaluated the currency.

During President Chavez’s time, oil was $100 a barrel. The resulting revenue generated was used by the government to fund social programs and food subsidies[vii]. However, declining revenues made such programs less feasible. Maduro government’s decision to expropriate many private companies, including General Motors[viii] in 2017, directly affected the manufacturing and production sectors and added to the country’s economic woes. The government today owns 526 businesses, most which have experienced a decline in production, contributing to the economic crisis[ix]. What has followed is hyperinflation that has plunged the country into a humanitarian emergency.

Source: Central Bank, BP Statistical Review of World Energy (2015)

Figure 2 (Oil Exports vs. Non-oil Exports[x])

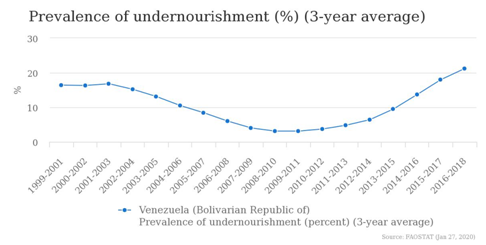

The 2017 National Survey of Living Condition, conducted by three Venezuelan universities, concluded that about a third of the country skipped meals because they could not afford eating three times a day. Another distressing observation was that three quarters of the people surveyed reported losing an average of 19 pounds of bodyweight between 2015-16[xi]. Between 2016-2018, 21.2% of Venezuelans were undernourished (Figure 3), a figure which has been increasing steadily since 2013.

Source: Venezuela (Bolivarian Republic of), Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (2018)

Figure 3 (Prevalence of undernourishment (%)[xii])

Even health facilities and services have suffered. There are not enough doctors or medicines to treat patients. Patients have been asked to bring their own medicines, syringes, latex gloves and even water[xiii]. Previously eradicated diseases like malaria, polio, measles and tuberculosis have re-emerged and basic and treatable infections are becoming harder to cure because of a lack of medical supplies[xiv]. In 2018, the government replaced the existing currency (Bolívar Fuerte) with the new Bolívar Soberano to reign in hyper-inflation and even hiked the minimum wage, but to no respite. The International Monetary Fund (IMF) estimates the inflation rate for 2020 to be a staggering 10 million percent[xv], resulting in further weakening of the purchasing power of ordinary Venezuelans and exacerbating the already widespread hunger and malnourishment.

In light of the conditions in Venezuela, international organisations such as the European Commission, the United Nations Central Emergency Response Fund, the World Health Organization (WHO) and the United Nations’ Children’s Fund have come to the rescue of Venezuelans by providing humanitarian aid in the form of food and medical and hygiene supplies. However, in February 2019, the Venezuelan government blocked attempts by opposition leader and self-proclaimed “interim president” Juan Guaidó to bring two US trucks carrying food and medical supplies into the country via the Colombian border town of Cucuta. President Maduro said that the US aid was just a way to humiliate the country and that if they really wanted to help, they should lift the sanctions[xvi]. In April, however, President Maduro softened his stance on foreign aid after a meeting with International Committee of the Red Cross’s (ICRC) president, Peter Maurer[xvii]. In fact, in 2019, the US was the biggest source of humanitarian funding for Venezuela, providing almost $60 million, according to UN data[xviii].

The relief funds to help the Venezuelans, however, are not enough and the crisis has resulted in a mass exodus, akin to the refugee crisis of Syria. According to World Bank data, around 4.6 million Venezuelan have fled the country to Colombia, Brazil, Ecuador, Bolivia, Mexico and even to the US and Spain[xix]. This amounts to a population dip of around 16%[xx].

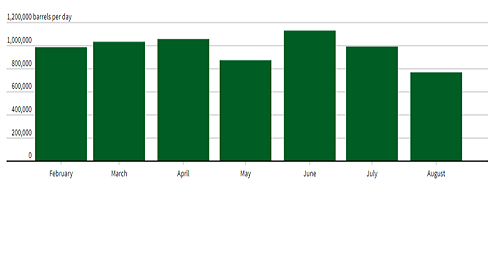

Source: Reuters Graphics (2019)

Figure 4 (Venezuela’s Oil Exports for 2019)[xxi]

After the US imposed sanctions on Venezuela in January 2019, a move designed to coerce President Maduro into giving up his office, its oil exports, which form 98 percent of its export earnings[xxii], further reduced, pressurising an economy still reeling from the after effects of the drop in oil prices. However, despite the sanctions, Russia’s Rosneft, China’s National Petroleum Corp (CNPC), Cuba’s Cubametales, India’s Reliance Industries and Spain’s Repsol continue to import Venezuelan oil, albeit in smaller quantities[xxiii].

The sanctions have made it harder for Venezuela to export oil. As a result, it has been forced to store it, resulting in storage units being filled to their capacity and forcing a reduction in production. Venezuela’s oil production is predicted to average a measly 600,000-800,000 barrels per day (bpd) in 2020[xxiv], a drop of around 40 percent from 2019.

In recent years, India has become an important oil purchaser for Venezuela. The current political turmoil in Venezuela has affected this bilateral trade relationship. The following section will have a look at the Indo-Venezuela political relationship before moving on to the Indo-Venezuela oil synergy, which forms the bulk of our dealings with Venezuela.

India-Venezuela Relations

Diplomatic relations between India and Venezuela were established in 1959 and Venezuela opened its embassy in New Delhi in 1962[xxv]. In 1968, the then Prime Minister Indira Gandhi visited the Andean nation as a part of her eight country Latin American and Caribbean (LAC) region tour[xxvi]. Due to geopolitical compulsions (the national emergency of the 70s in India and the ‘lost decade’ of the 80s in South America), the relations could not be developed to their potential. Nonetheless, President Hugo Chavez’s visit to India in the March of 2005 provided the much-needed impetus to reset the relations.

The relation between India and Venezuela is primarily driven by India’s demand for oil and Venezuela’s position as the country with the largest oil reserves in the world. There are some other non-oil related commercial exchanges between the countries, but they are small. India exports pharmaceuticals, calcined petroleum coke (CPC), textiles and automobiles to Venezuela[xxvii].

India-Venezuela Oil Relationship

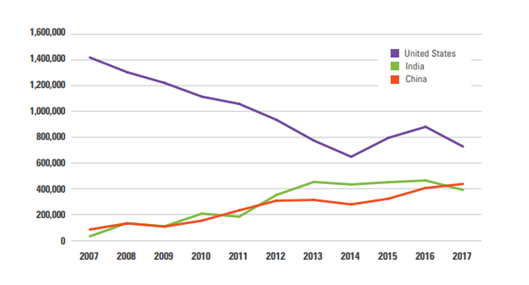

India’s rapid economic growth in the first decade of the 21st century meant that the demand for oil surged. Between 2005-2013, India’s oil imports almost doubled from 1.93 million barrels per day (bpd) to 3.88 million bpd[xxviii]. In 2008, India became the second largest importer of Venezuelan oil, second only to the US and narrowly edging out China (Figure 5) and today India is Asia’s biggest buyer of crude oil[xxix].

Source: Venezuela’s Exports to the United States, India, and China, Wilson Center (2019)

Figure 5 (Venezuela’s Oil Exports)[xxx]

India’s crude oil imports from Venezuela, apart from their commercial purpose, are also advantageous for the country. Venezuela is abundant in heavy crude oil, which is cheaper than the lighter grades of crude oil. Moreover, India has many refineries that are capable of processing heavy crude oil. Another advantage that the oil synergy with Venezuela has is that it helps to diversify India’s oil procurement and ensures that it does not depend solely on one region to meet its oil needs. India’s oil minister, Dharmendra Pradhan said in a 2014 interview that procurement has to be diversified, considering the changing geopolitics in the world. India will look to go to Russia and Latin America if that suits its needs.[xxxi]

As a result of the diversification policy, India’s imports from Latin American (Venezuela, Brazil and Mexico) and African nations (Angola and Nigeria)[xxxii] increased, decreasing the reliance on the Middle East. The US also became an important exporter to India, as India received 4% of its total oil exports in 2018[xxxiii].

It is evident that Venezuela is an important and advantageous oil partner for India and that the internal crisis in Venezuela will impact Indian interests. The following section aims to asses that.

Impact of the Venezuelan Crisis on India

|

Year |

India’s Oil Imports from Venezuela (US$ million) |

Growth % |

India’s Oil Imports from Venezuela (Quantity in thousand barrels per day) |

Growth % |

|

2013-14 |

13,936.59 |

-1.20 |

21,304.51 |

-65.17 |

|

2014-15 |

11,669.14 |

-16.27 |

22,884.57 |

7.42 |

|

2015-16 |

5678.63 |

-51.34 |

22,721.00 |

-0.71 |

|

2016-17 |

5,505.88 |

-3.04 |

21,439.16 |

-5.64 |

|

2017-18 |

5,859.40 |

6.42 |

18,349.46 |

-14.41 |

|

2018-19 |

7,248.15 |

23.70 |

17,324.07 |

-5.59 |

|

2019-20 (Apr-Nov) |

3,545.34 |

-51.09 |

9589.18 |

-44.64 |

Source: Department of Commerce, Government of India (2020)

Table 1 (India’s Oil Imports from Venezuela[xxxiv])

Beginning 2014, India’s imports decreased in value. This can be attributed to the decrease in oil prices in June 2014, which also marked the beginning of the Venezuelan crisis as we know it today. Further drop in prices led to a reduction in trade in terms of value (but not volume) in 2015-16. Since then, a consistent decrease in the quantity of oil imported is evident. After the imposition of the US sanction in January 2019, the import reduced drastically. This can be attributed to a four-month hiatus during which Reliance Industries halted oil imports from Venezuela after pressure from the US. In October, Reliance resumed its operations in a barter deal where it will pay in diesel for the oil[xxxv].

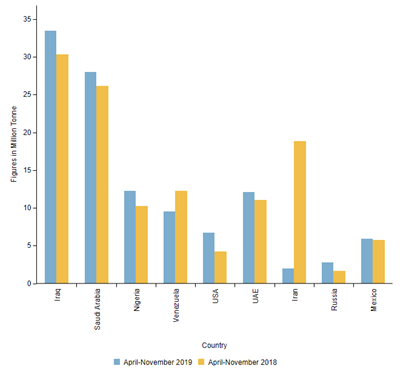

It can be concluded that the crisis in Venezuela has affected the India-Venezuela bilateral oil trade. This is worrying for Venezuela as it owes a $60 billion debt to China. India generated $7.39 billion in revenue for Venezuela in 2018[xxxvi] and Venezuela would have wanted to increase this in 2019 to pay off a part of its huge debt. India, to make up for the loss in Venezuelan imports, increased its oil imports from the US, UAE, Nigeria and Iraq and even imported Venezuelan oil from Russia’s Rosneft (Figure 6). The dwindling oil production levels in Venezuela have also proven to be a source of worry for ONGC Videsh Ltd (OVL), the foreign arm of ONGC. The Indovenezolana joint venture between OVL and PDVSA produces a meagre 9,900 bpd of extra crude oil, against the expected 40,000 bpd. This has happened because of the lack of tankers for exporting (due to the US sanctions) because of which there is surplus oil in the storage tanks and hence more oil cannot be produced. Production has also declined due to the frequent blackouts caused by a deteriorating power grid[xxxvii]. Moreover, a struggling PDVSA also owes $449 million worth of accrued dividends to the OVL for its 40 percent stake in the San Cristobal fields[xxxviii].

Source: India’s oil imports from Iraq, Nigeria and UAE increase in Nov 2019, EnergyWorld (2019)

Figure 6 (India’s Oil Imports)[xxxix]

|

Year |

India’s Exports to Venezuela (US$ million) |

Growth % |

|

2013-14 |

196.96 |

-15.88 |

|

2014-15 |

258.07 |

31.02 |

|

2015-16 |

130.66 |

-49.37 |

|

2016-17 |

62.22 |

-52.38 |

|

2017-18 |

79.21 |

27.30 |

|

2018-19 |

164.77 |

10.80 |

|

2019-20 (Apr-Nov) |

131.40 |

-20.25 |

Source: Department of Commerce, Government of India (2020)

Table 2 (India’s Exports to Venezuela[xl])

Indian exports to Venezuela, which are mainly pharmaceuticals have also experienced a decline. This could be because of the foreign currency crunch and because Venezuela owes Indian pharmaceutical companies, Dr. Reddy’s Laboratories, Glenmark Pharmaceuticals, Claris Lifesciences, and Sun Pharmaceutical Industries $350 million as the Maduro government has not allowed repatriation of money by subsidiaries to their overseas parent companies[xli]. This would have made these companies reluctant to export their goods.

Conclusion

India’s relationship with Venezuela is primarily based on oil and under the present circumstances it is unlikely to deepen in the near future. For India, Brazil and Mexico continue to hold more importance in the Latin American and Caribbean (LAC) region and this is likely to continue for the foreseeable future. Similarly, for Caracas, Moscow, Beijing and Havana are important political and ideological allies.

The political and economic crisis in Venezuela has meant that India has started looking to other nations of the region for energy resources. However, if global oil prices increase again, Venezuela’s economy will recover and the commercial relationship between the two countries will resume. As India’s oil demands grow and because Venezuelan crude oil is more economical than the lighter grade African variety and Venezuela possesses bigger oil reserves than Africa, it is important for New Delhi maintain a stable but apolitical relationship with Caracas.

*****

*Reetinder Kaur Chowdhary, Research Intern, Indian Council of World Affairs.

Disclaimer: Views expressed are personal.

Endnotes

[i]Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries. OPEC Oil Reserves, Available on: https://www.opec.org/opec_web/en/data_graphs/330.htm. Accessed on January 10, 2020.

[ii]Borger, Julian, “Venezuela at the crossroads: the who, what and why of the crisis”, The Guardian, January 25, 2019, Available on: https://www.theguardian.com/world/2019/jan/25/venezuela-explainer-crisis-maduro-guaido-what-is-happening-latest, Accessed on: January 11, 2020.

[iii]Ellsworth, Brian and Ore, Diego, “Venezuela opposition demands vote recount, protests flare”, Reuters, April 15, 2013, Available on: https://www.reuters.com/article/us-venezuela-election/venezuela-opposition-demands-vote-recount-protests-flare-idUSBRE93C0B120130415. Accessed on January 10, 2020.

[iv]International Monetary Fund. Available on: https://www.imf.org/en/Countries/VEN#countrydata. Accessed on January 13, 2020.

[v]Kiger, Patrick, “How Venezuela Fell From the Richest Country in South America into Crisis”, History, May 9, 2019, Available on: https://www.history.com/news/venezuela-chavez-maduro-crisis. Accessed on January 13, 2020.

[vi] ITC Trade Map, Available on: https://www.trademap.org/Product_SelCountry_TS.aspx?nvpm=1%7c862%7c%7c%7c%7cTOTAL%7c%7c%7c2%7c1%7c1%7c1%7c2%7c1%7c1%7c1%7c. Accessed on January 13, 2020.

[vii]Sanchez, Ray, “Venezuela: How paradise got lost”, CNN, July 27, 2017, Available on: https://edition.cnn.com/2017/04/21/americas/venezuela-crisis-explained/index.html. Accessed on January 24, 2020.

[viii]Kurmanaev, Anatoly; Vyas, Kejal and Colias, Mike, “GM Ceases Operation in Venezuela as Plant is Expropriated”, Fox Business, April 20, 2017, Available on: https://www.foxbusiness.com/markets/gm-ceases-operation-in-venezuela-as-plant-is-expropriated. Accessed on January 24, 2020.

[ix]Camacho, Carlos, “Why Venezuela Now Has 526 State-Owned Companies”, Latin American Herald, January 24, 2020, Available on: http://www.laht.com/article.asp?CategoryId=10717&ArticleId=2443983. Accessed on January 24, 2020.

[x]“The Impact of the Decline in Oil Prices on the Economics, Politics and Oil Industry of Venezuela”, Center on Global Energy Policy, Available on: https://energypolicy.columbia.edu/sites/default/files/Impact%20of%20the%20Decline%20in%20Oil%20Prices%20on%20Venezuela_September%202015.pdf. Accessed on January 13, 2020.

[xi]Aleem, Zeeshan, “Venezuela’s economic crisis is so dire that most people have lost an average of 19 pounds”, Vox, February 22, 2017, Available on: https://www.vox.com/world/2017/2/22/14688194/venezuela-crisis-study-food-shortage. Accessed on January 13, 2020.

[xii]Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, Available on: http://www.fao.org/faostat/en/#country/236. Accessed on January 27, 2020.

[xiii]Phillips, Tom, “Venezuela crisis takes deadly toll on buckling health system”, The Guardian, January 6, 2019, Available on: https://www.theguardian.com/world/2019/jan/06/venezuela-health-system-crisis-nicolas-maduro. Accessed on January 13, 2020.

[xiv]Daniel, Zoe and Lenihan, Niall, “Venezuelans are slowly starving to death as Maduro and Guaido battle for power”, ABC News, June 13, 2019, Available on: https://www.abc.net.au/news/2019-06-12/venezuelans-starving-as-country-gripped-by-economic-crisis/11197560. Accessed on January 24, 2019.

[xv]International Monetary Fund. Available on: https://www.imf.org/external/datamapper/ngdpdpc[at]weo/VEN/BRA. Accessed on January 13, 2020.

[xvi] Soares, Isa; Gallon, Nathalie and Smith-Spark, Laura, “Tensions rise as Venezuela blocks border bridge in standoff over aid”, CNN, February 9, 2019, Available on: https://edition.cnn.com/2019/02/07/americas/venezuela-aid-blocked-bridge-intl/index.html. Accessed on January 27, 2020.

[xvii] Melimpoulos, Elizabeth, “Maduro says Venezuela ready to receive international aid”, Al Jazeera, April 10, 2019, Available on: https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2019/04/maduro-venezuela-ready-receive-international-aid-190410083550252.html. Accessed on January 27, 2020.

[xviii]Financial Tracking Service, Bolivarian Republic of Venezuela, Available on: https://fts.unocha.org/countries/242/summary/2019. Accessed on January 27, 2020.

[xix]The World Bank. Venezuelan Migration: The 4,500-Kilometer Gap Between Desperation and Opportunity. Available on: https://www.worldbank.org/en/news/feature/2019/11/26/migracion-venezolana-4500-kilometros-entre-el-abandono-y-la-oportunidad. Accessed on January 14, 2020.

[xx]Worldometer. Available on:https://www.worldometers.info/world-population/venezuela-population/. Accessed on February 27, 2020.

[xxi]Reuters Graphics. Available on: https://fingfx.thomsonreuters.com/gfx/editorcharts/VENEZUELA-OIL-EXPORTS/0H001QETK86L/index.html. Accessed on January 15, 2020.

[xxii]Ellyatt, Holly, “Oil markets face three possible scenarios in Venezuela”, CNBC, May 2, 2019, Available on: https://www.cnbc.com/2019/05/02/venezuela-crisis-and-how-it-could-affect-oil.html. Accessed on January 14, 2020.

[xxiii]Parraga, Marianna, “Venezuelan oil exports fell by a third in 2019 as U.S. sanctions bit -data”, Nasdaq, January 7, 2020, Available on: https://www.nasdaq.com/articles/venezuelan-oil-exports-fell-by-a-third-in-2019-as-u.s.-sanctions-bit-data-2020-01-07. Accessed on January 28, 2020.

[xxiv]Ibid.

[xxv] Ministry of External Affairs, Annual Report 1961–62, Government of India, Available on: https://mealib.nic.in/?pdf2488?000. Accessed on January 14, 2020.

[xxvi]Embassy of India in Venezuela. Indira Gandhi in Venezuela (1968–2013): 45th Anniversary of a Historic Visit, Available on: http://www.eoicaracas.gov.in/docs/IndiraGandhiVisit.pdf. Accessed on January 14, 2020.

[xxvii]Ibid.

[xxviii]“India-Venezuela Relations: A Case Study in Oil Diplomacy “, Wilson Center, February, 2019, Available on: https://www.wilsoncenter.org/sites/default/files/india-venezuela_relations_final_0.pdf. Accessed on January 15, 2017.

[xxix]Ibid

[xxx]Supra note 28.

[xxxi]Chakraborty, Debjit and Katakey, Rakteem, “India Plans to Diversify Oil Imports”, Live Mint, October 25, 2014, Available on: https://www.livemint.com/Politics/dtqX201kKrlYSwlaNuuH5N/India-plans-to-diversify-oil-imports.html. Accessed on January 14, 2020.

[xxxii]Ibid.

[xxxiii] ITC Trade Map, Available on: https://www.trademap.org/Bilateral_TS.aspx?nvpm=1%7c699%7c%7c842%7c%7c2710%7c%7c%7c4%7c1%7c1%7c1%7c2%7c1%7c1%7c2%7c1. Accessed on January 14, 2020.

[xxxiv]Department of Commerce, Available on: https://commerce-app.gov.in/eidb/Icntcom.asp. Accessed on January 27, 2020.

[xxxv]Supra note 22.

[xxxvi]Seshasayee, Hari, “India and Venezuela Grow Distant Post U.S.-Sanctions”, Wilson Center, August 5, 2019, Available on: https://www.wilsoncenter.org/article/india-and-venezuela-grow-distant-post-us-sanctions. Accessed on January 15, 2020.

[xxxvii]“Venezuela's Orinoco Belt crude production falls to 169,800 b/d”, S&P Global Platts, May 14, 2019, Available on: https://www.spglobal.com/platts/en/market-insights/latest-news/oil/051419-venezuelas-orinoco-belt-crude-production-falls-to-169800-b-d. Accessed on January 15, 2020.

[xxxviii]“OVL declines Venezuela’s offer for additional stake in oilfield”, Financial Express, September 9, 2018, Available on: https://www.financialexpress.com/industry/ovl-declines-venezuelas-offer-for-additional-stake-in-oilfield/1307239/. Accessed on January 15, 2020.

[xxxix]Abdi, Bilal, “India’s oil imports from Iraq, Nigeria and UAE increase in Nov 2019”, Energy World, January 13, 2020, Available on: https://energy.economictimes.indiatimes.com/news/oil-and-gas/indias-oil-imports-from-iraq-nigeria-and-uae-increase-in-nov-2019/73226587. Accessed on January 15, 2020.

[xl]Supra note 34.

[xli]Jacob Shine, “Venezuela knocks on FinMin, State Bank of India doors for rupee trade”, Business Standard, May 29, 2018, Available on: https://www.business-standard.com/article/economy-policy/venezuela-knocks-finance-ministry-sbi-doors-for-rupee-trade-with-india-118052801326_1.html.Accessed on January 15, 2020.